Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Spotlight on Kim Smith

-

Interview

- 1. Landing a job at ILM

- 2. Model-making influences

- 3. A day in the ILM model shop

- 4. Crafting the USS Enterprise

- 5. Unique model-making techniques

- 6. Most challenging model

- 7. Transition to digital effects

- 8. Working at Tippett Studio

- 9. Starship Troopers contribution

- 10. Practical vs. digital effects

- 11. Legacy of practical models

- 12. Returning to the industry

- Photos of Kim’s Work

Introduction

In February 2025, we had the honor of conducting an exclusive interview with Kim Smith, a renowned model maker and digital artist. With an extensive career at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and Tippett Studio, Kim has contributed to some of the most iconic visual effects in cinema history. She shared insights into her journey, the art of model-making, and her experience transitioning into the digital effects world.

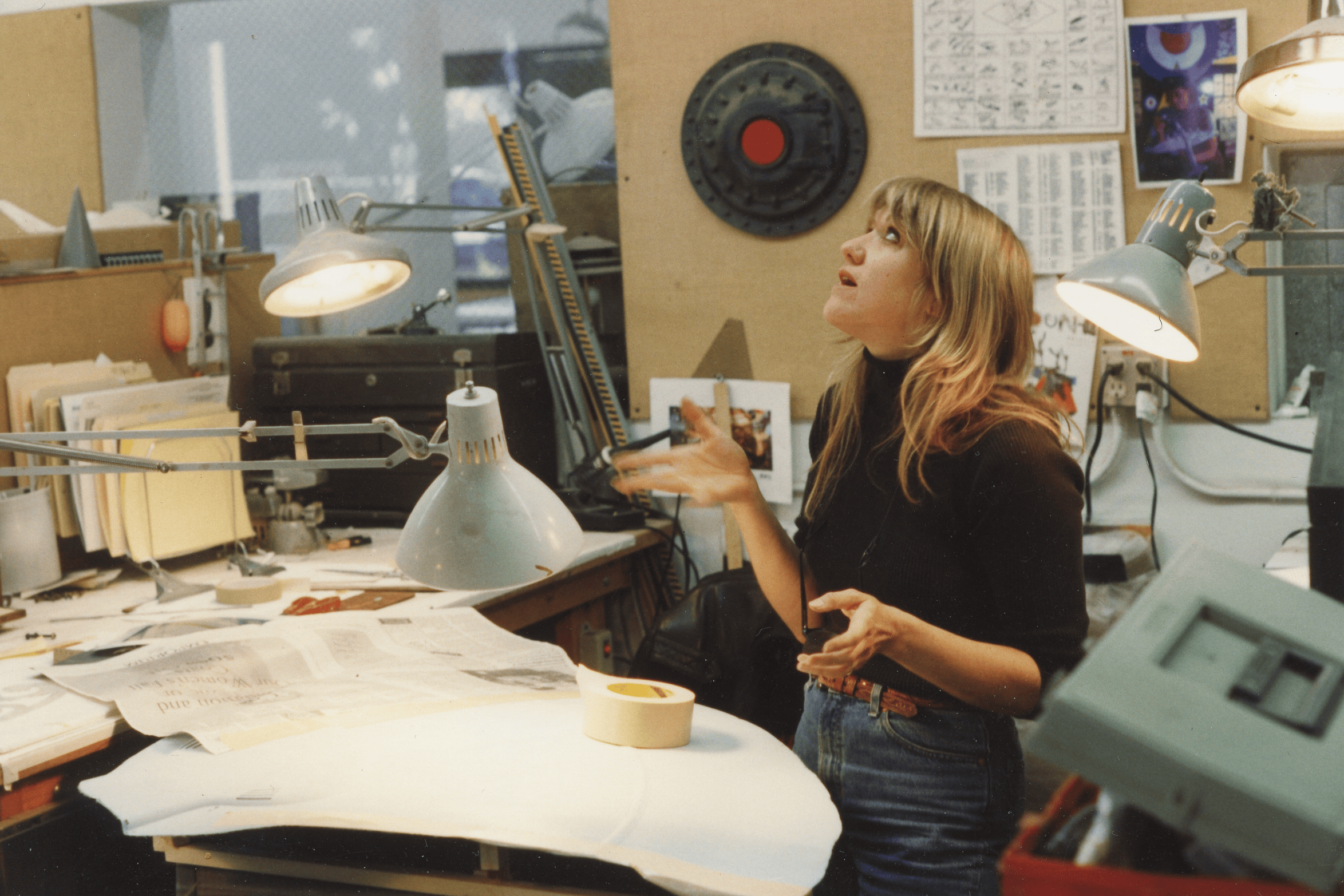

Spotlight on Kim Smith

From Practical Models to Digital Art

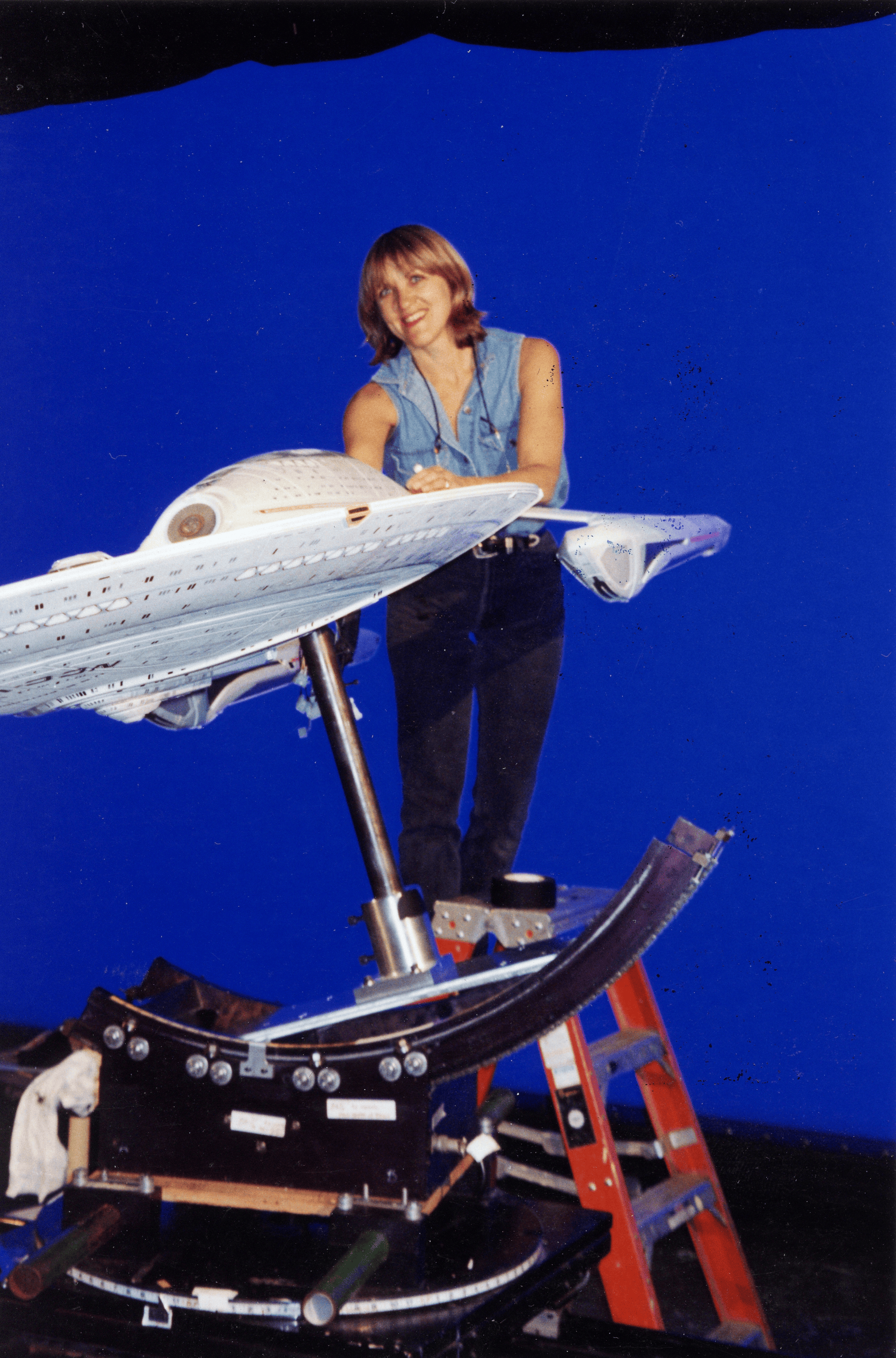

Kim Smith’s artistic journey began with traditional model-making, where she played a key role in crafting miniatures for blockbuster films. Her expertise in physical models, painting, and textures contributed to the realism of spaceships, environments, and props on screen.

Industrial Light & Magic and the Art of Model-Making

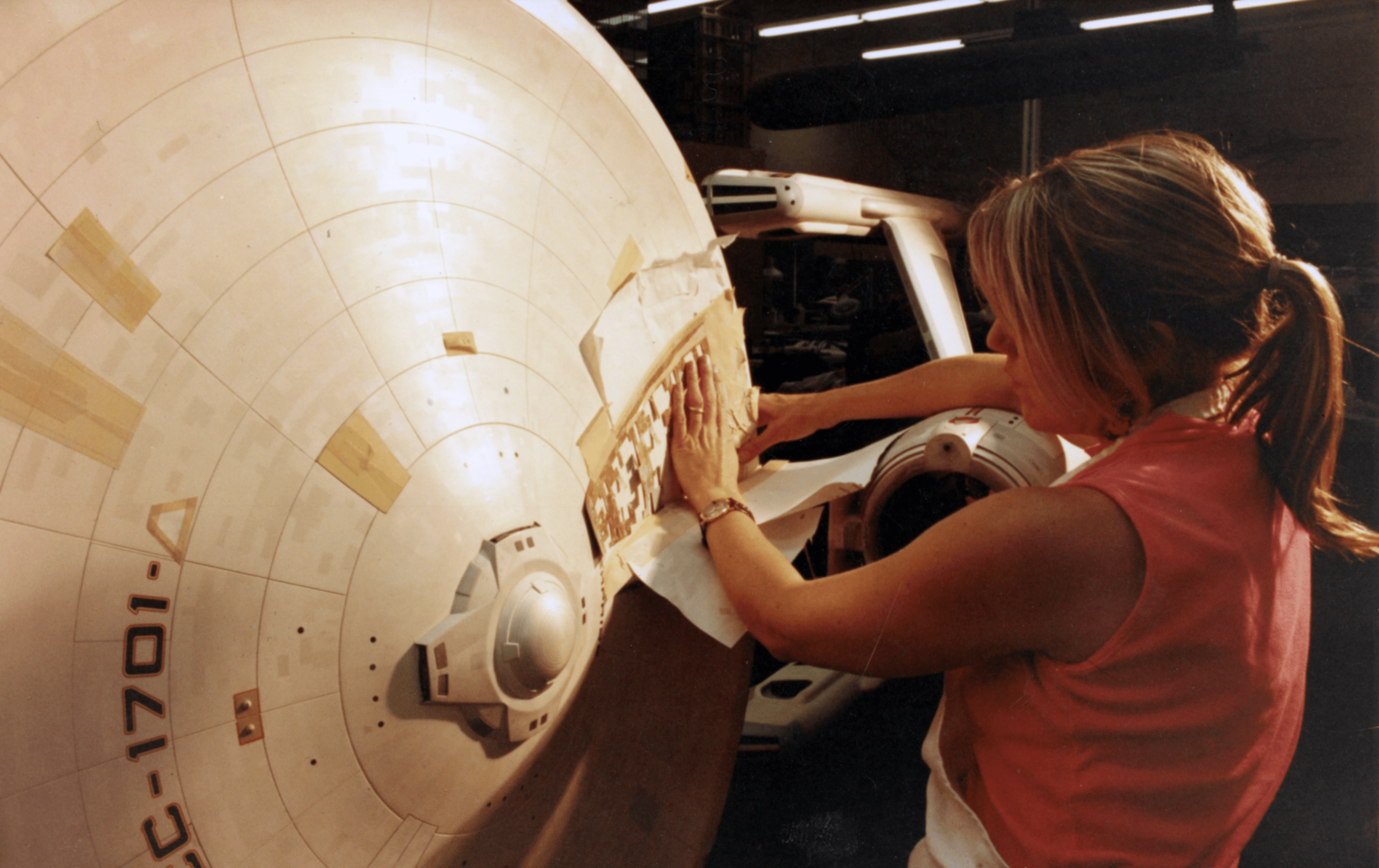

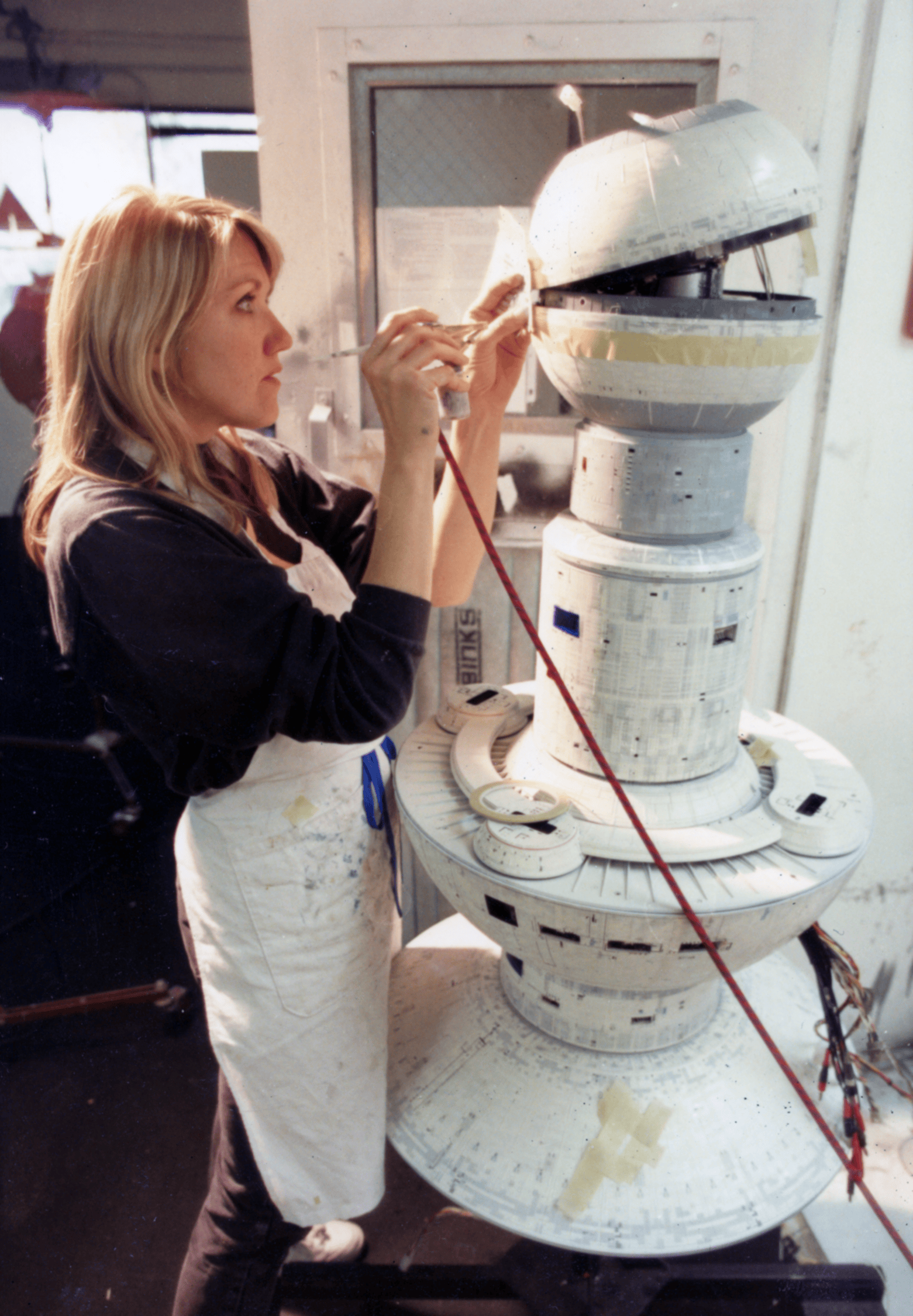

During her tenure at ILM, Kim worked on numerous high-profile projects, including Star Trek films, where she helped bring the USS Enterprise to life. Her attention to detail and ability to create believable textures made her a vital part of the model shop.

Transitioning to Digital Effects

As the film industry shifted from practical models to CGI, Kim adapted her skills, moving into digital texture painting and look development at Tippett Studio. Her experience with physical materials gave her a unique perspective on digital work, allowing her to create more lifelike CGI models.

Interview with Kim Smith

The ILM model shop was looking for people to work on a film for Epcot called “Body Wars”. I had applied right at that same time to work on a Kurosawa movie “Dreams” but they were not ready to start work on “Dreams”. Instead, I got hired to work on “Body Wars”.

I got hired right away after applying just because I applied at a “lucky” time when they needed lots of people. I had a good portfolio of miniatures from having worked at Landmark Entertainment in Los Angeles for several years. Getting a job at ILM was a coveted position, and I managed to show up at the right time, much to the chagrin of several LA colleagues.

I can’t say I had any particular mentor. From Landmark, I had a pretty good background in miniatures; painting, sculpting, textile, and also some light construction on sets and props. At both Landmark and ILM we all picked up techniques from each other. John Goodson would be the person I probably learned the most from, as we worked most closely. He had his techniques for model building and detailing, and he probably learned something from me about color mixing and paint.

We worked regularly as a team on a great many projects, along with a couple of other people, so there was lots of opportunity to learn from each other. Lorne Peterson, Steve Gawley, Larry Tan, Bill George, Charlie Bailey, Barbara Affonso, Randy Ottenberg, and many others were also very generous in passing on legacy techniques.

I sort of stumbled into making miniatures. I had been interested in creating my own tiny environments as a child and because I had broad artistic experience as an adult, was able to adapt to the model shop environment well. Surprisingly, I employed some techniques for painting that my father, an illustrator, used himself, and they were very effective. Those techniques began being used elsewhere in the shop by other people.

Thus, my “learning the craft of model-making” was quite organic. I had a feel for both hard-surface and organic shapes, for some reason. I always was fascinated by hardware and also loved animals; loved sculpting and drawing them.

It was very high-pressure. There were times we did not go home for a few days. In terms of personal interactions, if you were not a team player, you did not last long. We sometimes had five or six people working in a tiny area and egos needed to be left at home, though there were tensions at times, naturally.

Very ambitious or high maintenance people were difficult and not appreciated by the rest of the crew. We all were expected to do whatever needed to be done, even menial or beginner-level jobs. Sometimes new people refused to do the menial jobs that very experienced and long-time people would gladly do if needed. Those newcomers did not last.

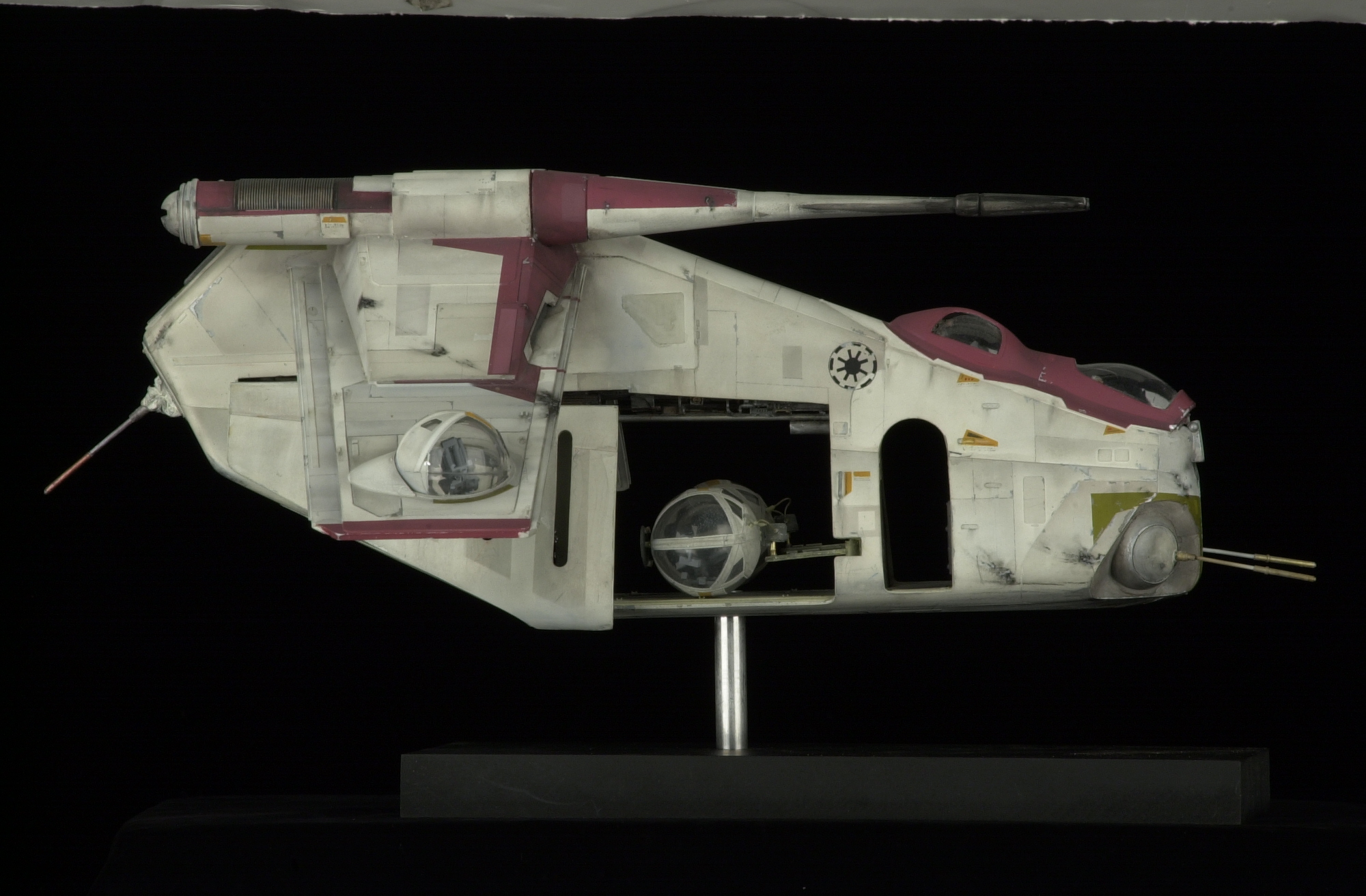

Lots of fine detail on a miniature makes the scale of the ship seem bigger on film. The break-up of the specular panels does the same. If there is no tiny detail and no specular breakup, the ship will look like a toy. In real life, a large object reflects quite a lot around it, even matte objects reflect a lot. And, for example, planes, especially older planes, have a lot of wow in the surface. Aging and weathering add scale, especially when done with an even hand. A heavy hand with some kinds of streaking can make it look painted rather than natural, and you have to use the correct colors of aging to sell the scale.

People often want to use black, which is usually not as good as deep warm or cool greys and browns. We ask ourselves “What is the motivation for the aging”? Is it organic, in which case it might be on the green side; oily, which might be on the warm deep brown side, or a light grey from ash or certain kinds of dirt. Is the aging affected by wind? When painting masonry, observing how water collects and flows, or even “backs up” will give you the motivation for aging.

That being said, for space ships we did sometimes age them intentionally as if they might land on earth occasionally, rather than the non-obvious aging that would happen in space. It sold the scale, even if it was not strictly what would happen in space.

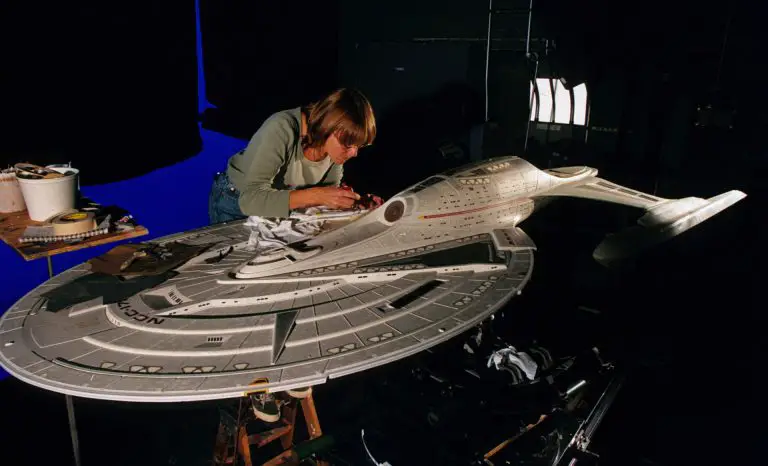

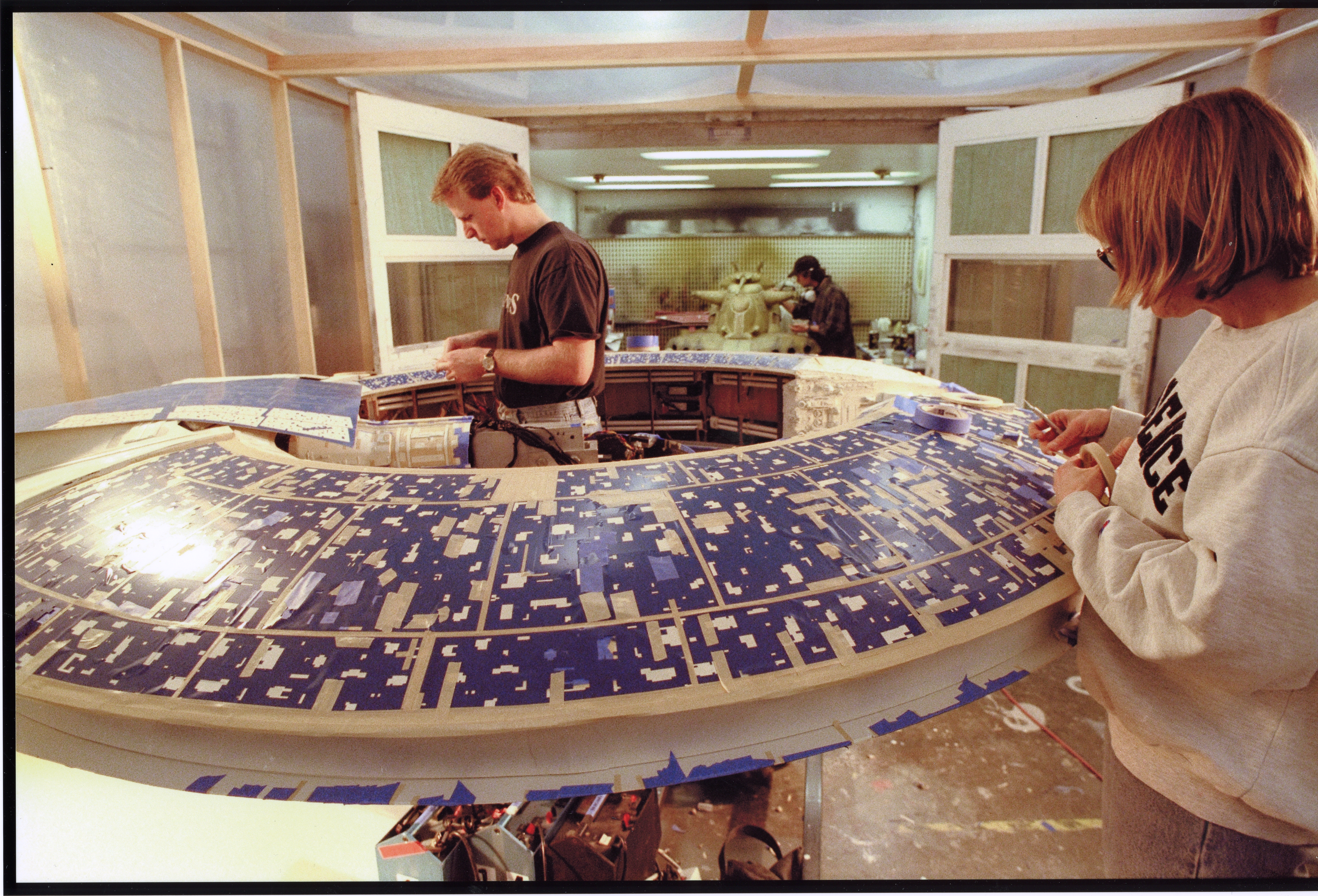

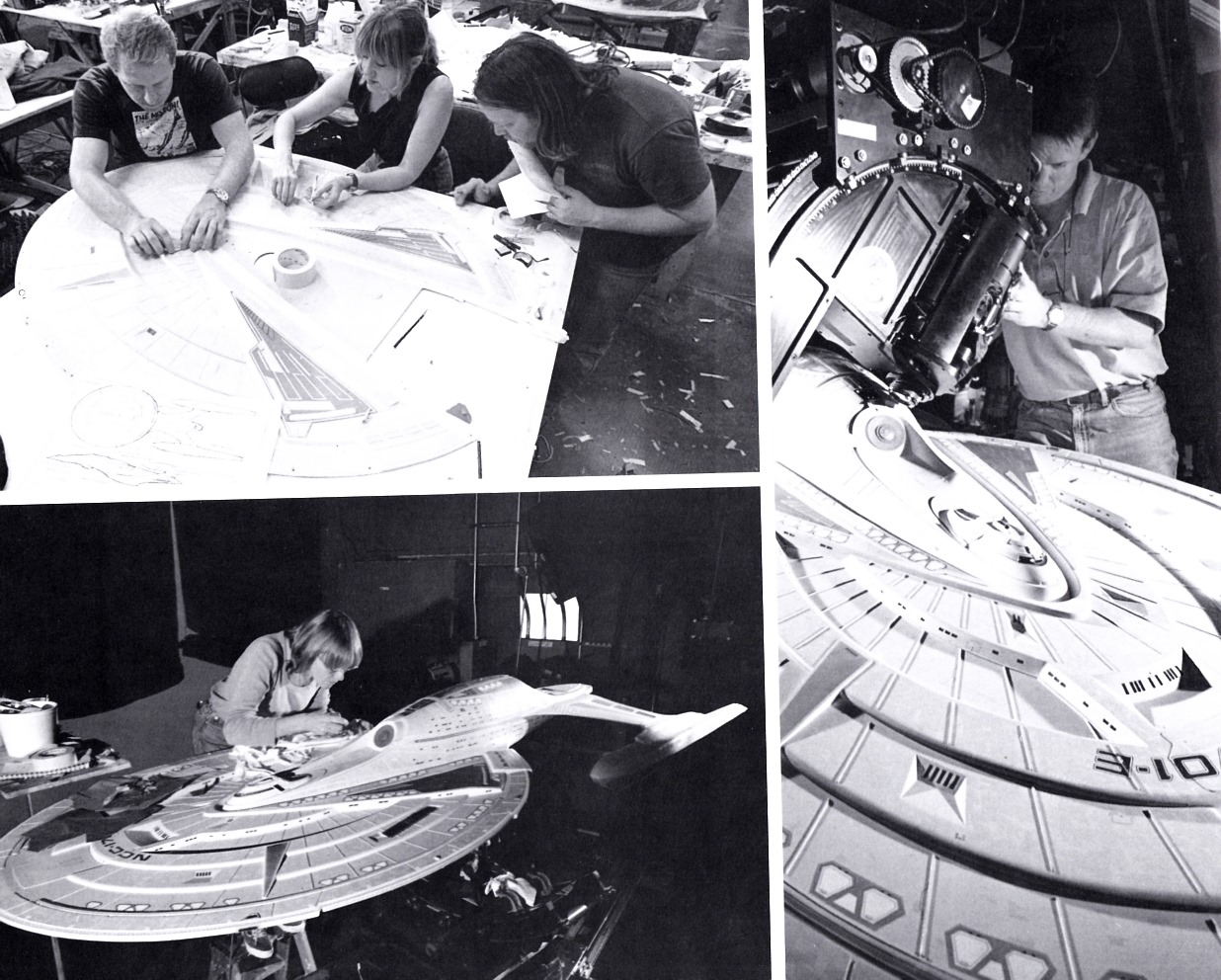

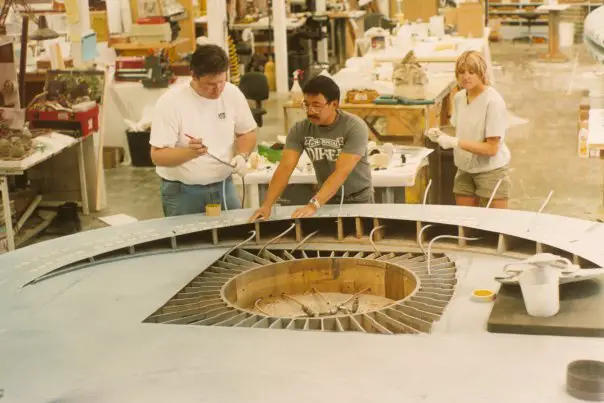

On the Federation Battleship we added thousands of tiny styrene chips to sell the huge scale of that ship, as the camera was going to get very close. Days of adding tiny chips. On the Enterprise ships we also added transfer type; sometimes small lines.

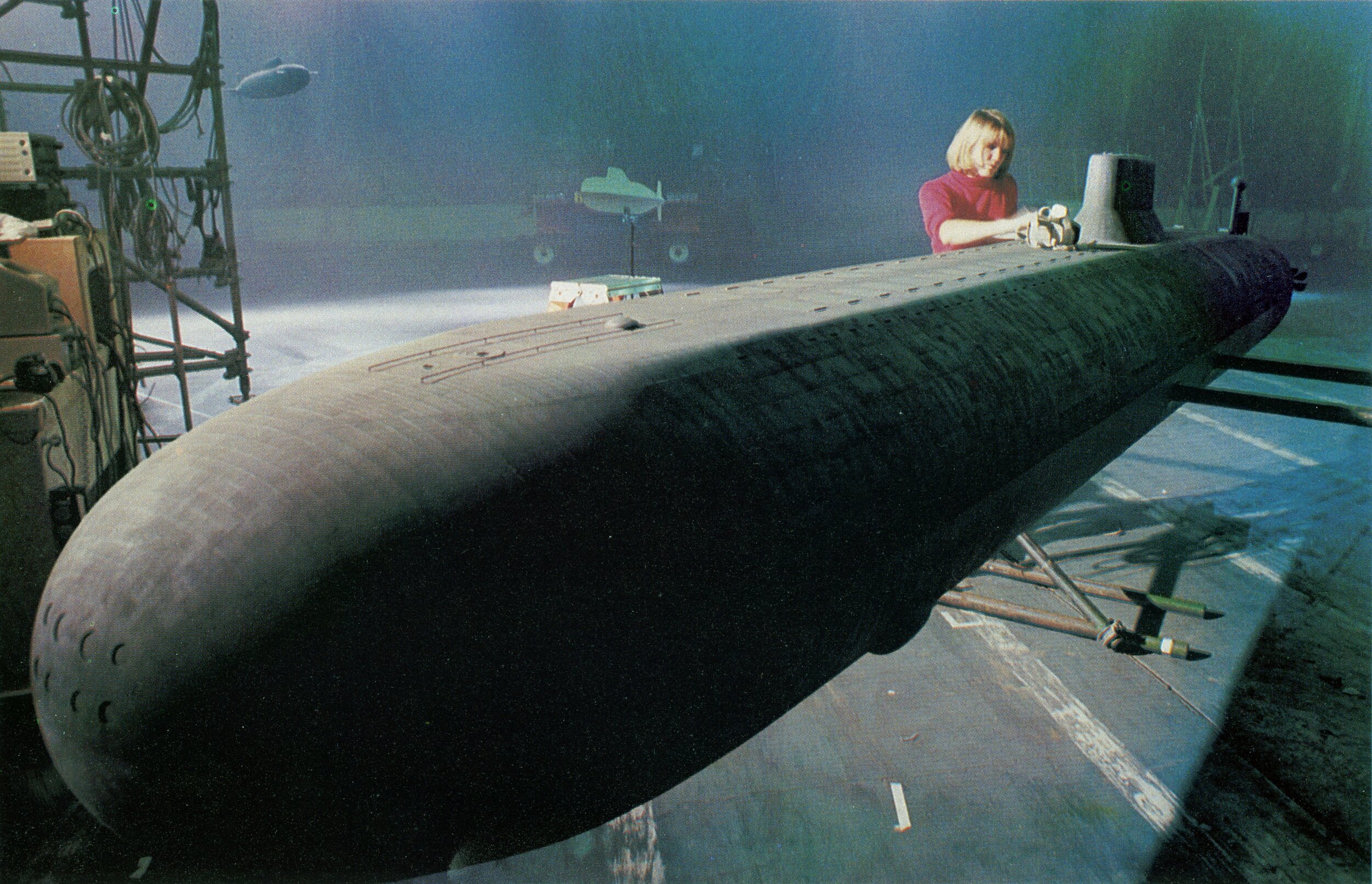

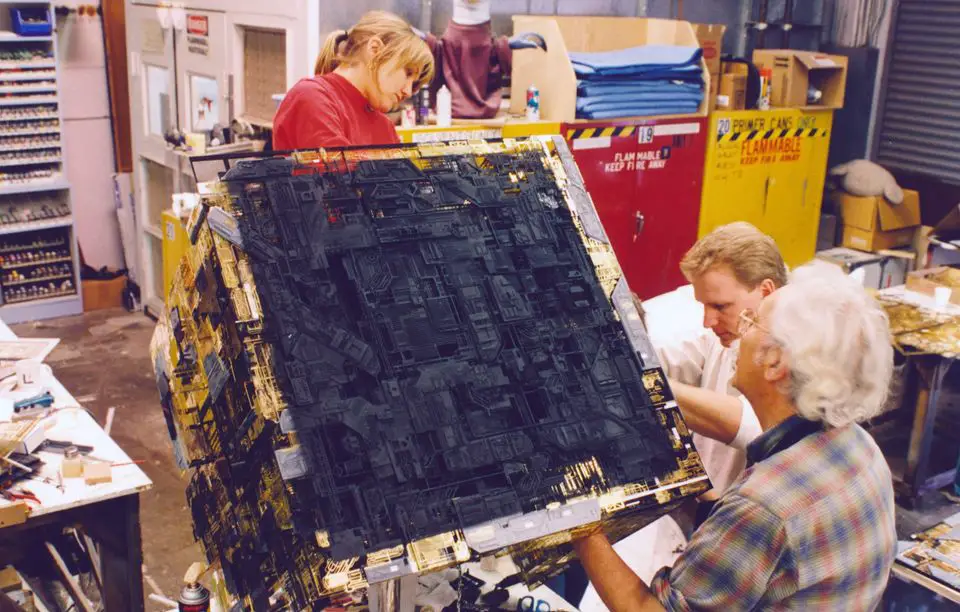

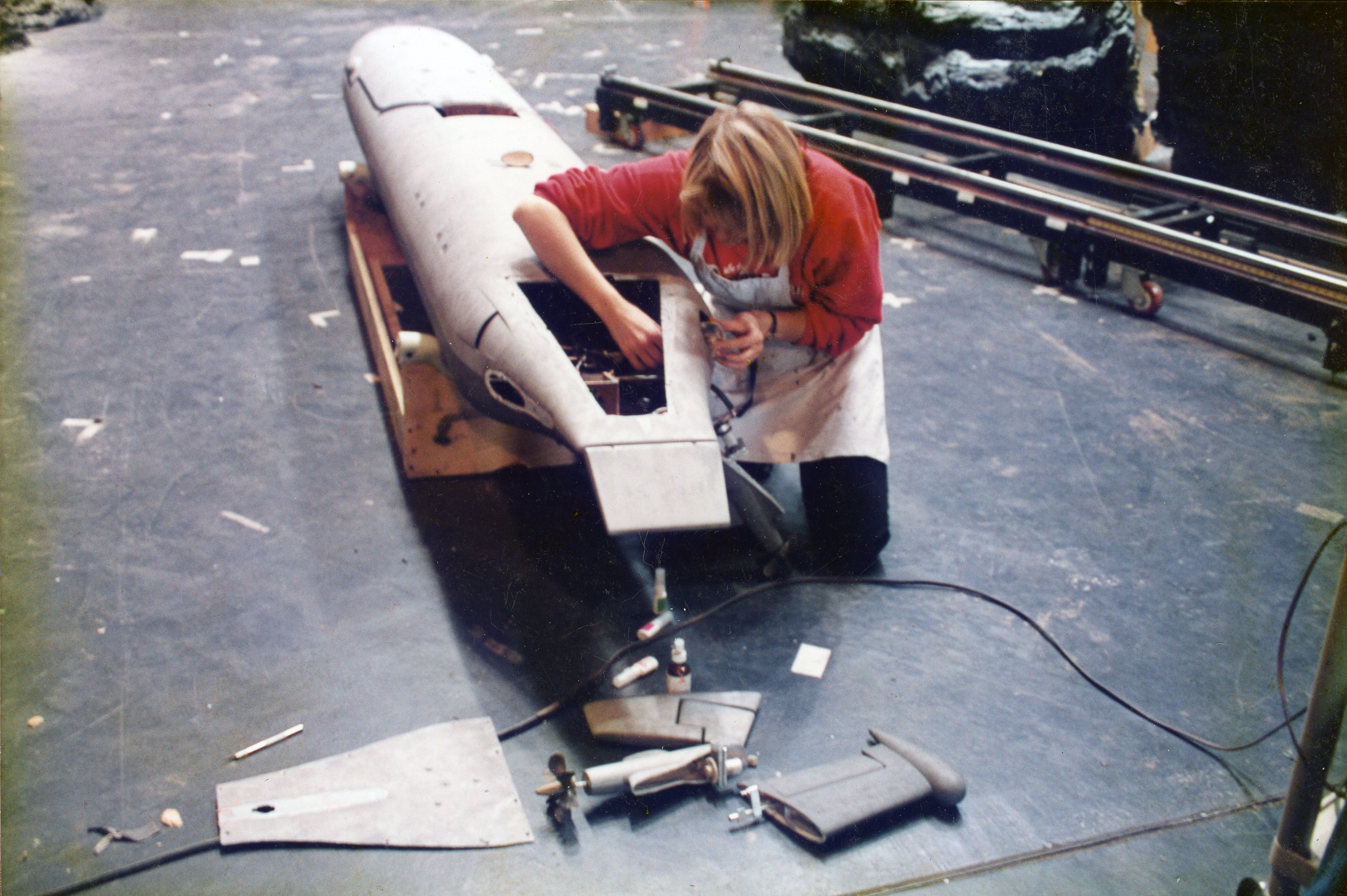

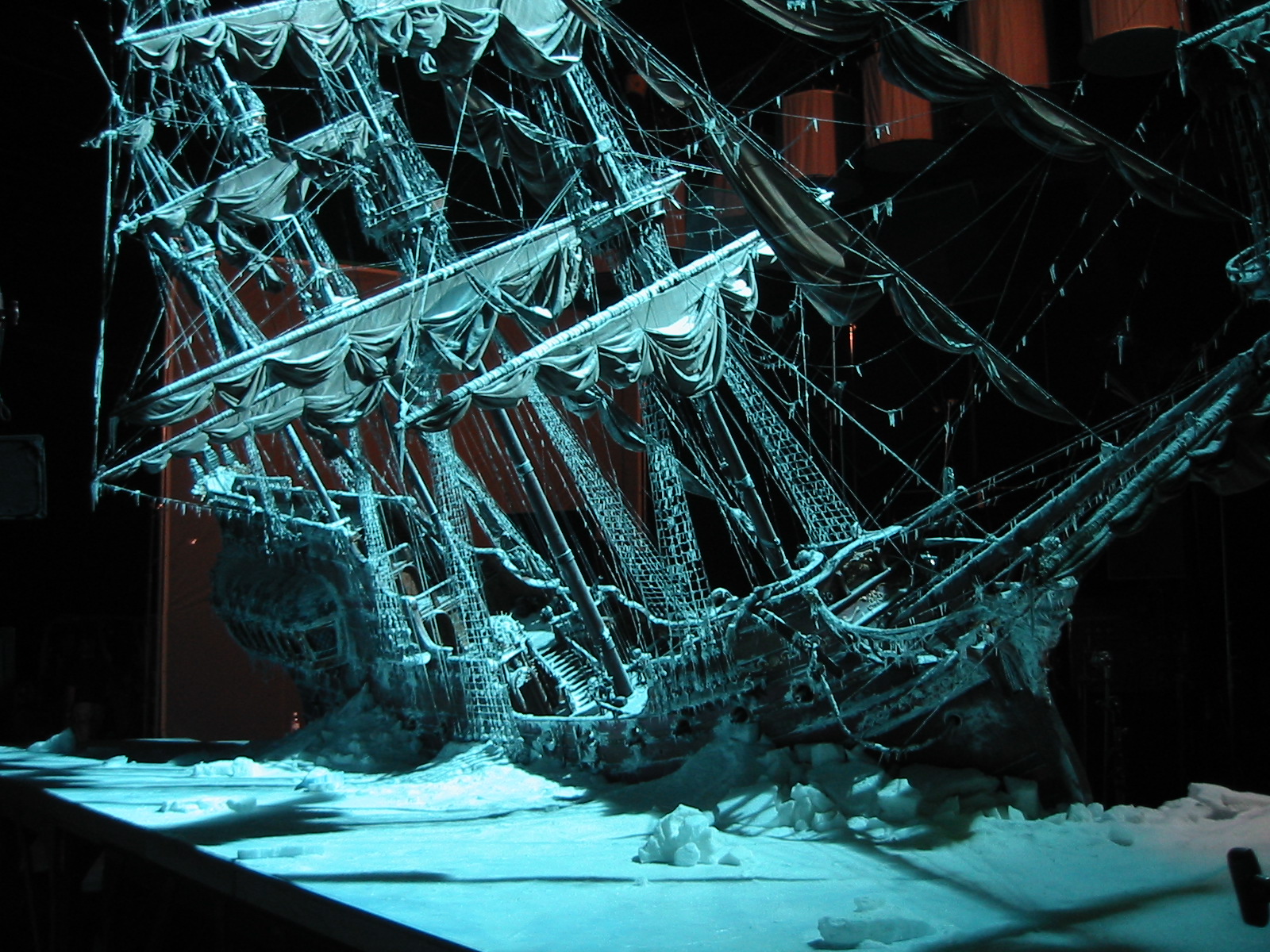

A couple of specific things I invented or re-invented for myself. One was using masking fluid to create the textures for the surfacing of the submarines for “The Hunt for Red October”. No doubt people have used latex or masking fluid in our industry, but the method I developed was fairly specific. I think it was reused on other ships such as the Protector miniature we made for Galaxy Quest.

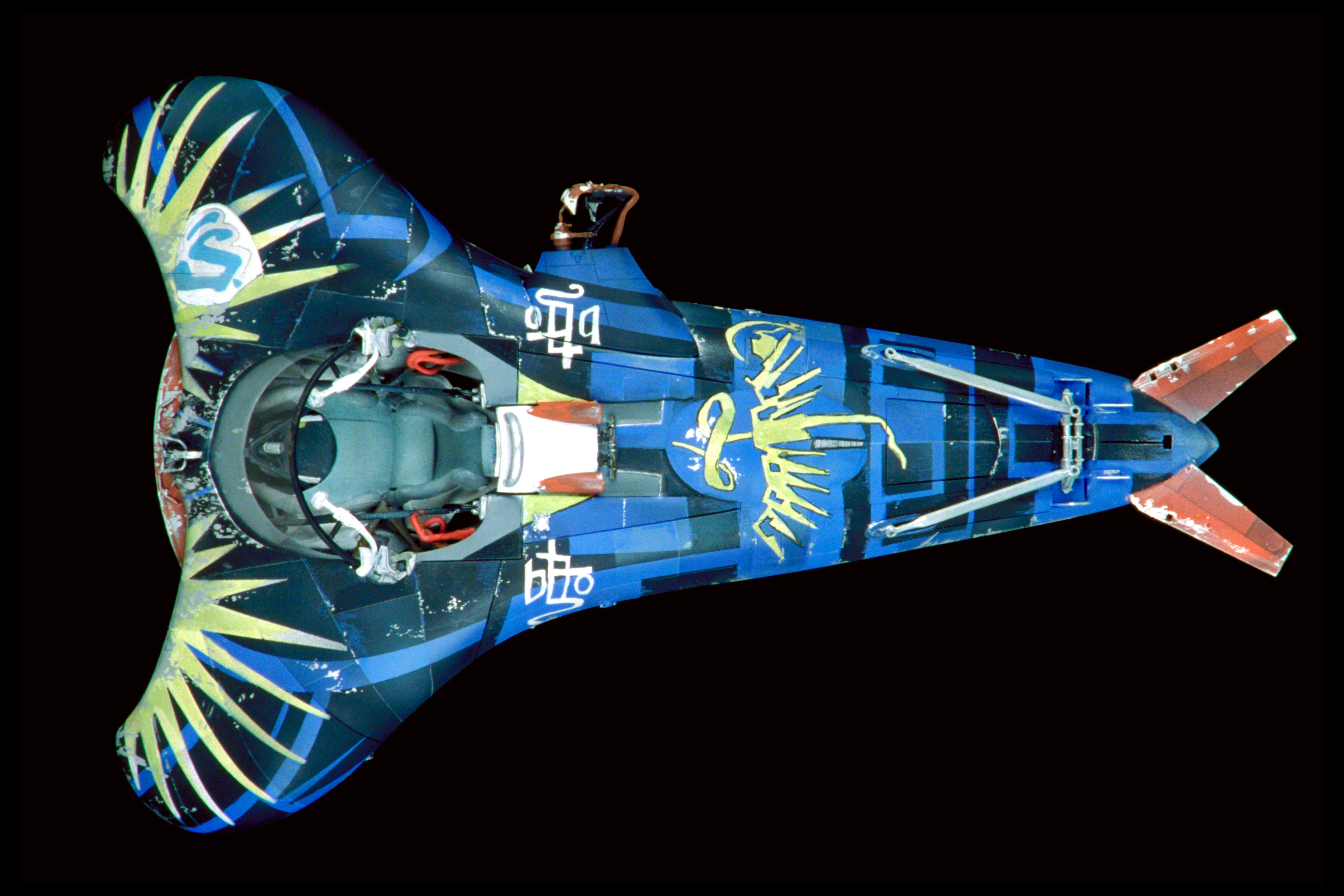

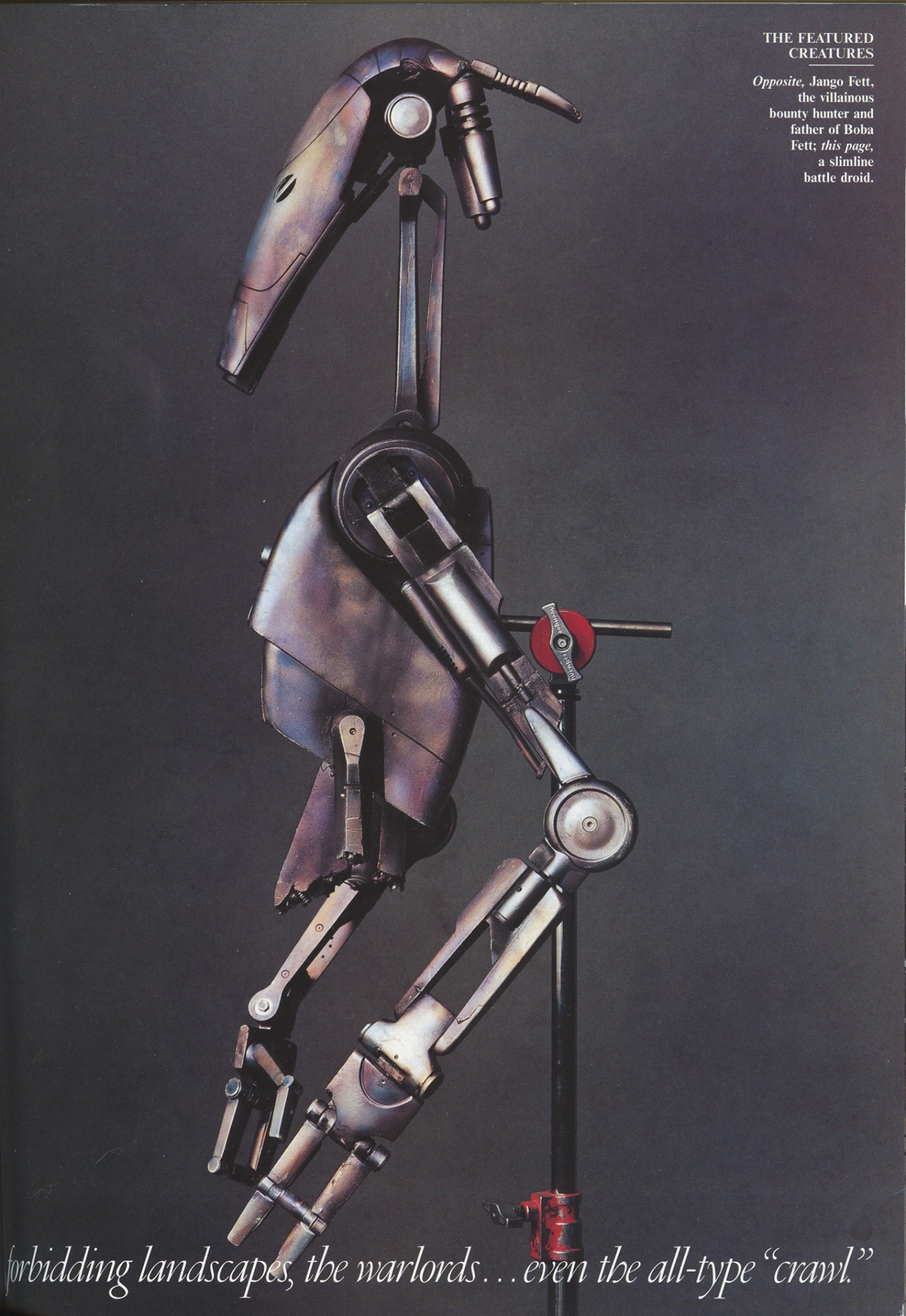

I developed my own method for painting oxidized or burnt metals, first for an Intel commercial (interior of a computer case), then for a droid lighting test piece for Star Wars: Attack of the Clones. No doubt others developed similar methods on their own, but I developed my method without influence. My lighting droid was photographed for Vanity Fair by Annie Leibovitz!

Every project required invention. Experience informed our solutions, but no two projects were alike. We were good problem-solvers; a team that could attack on all levels.

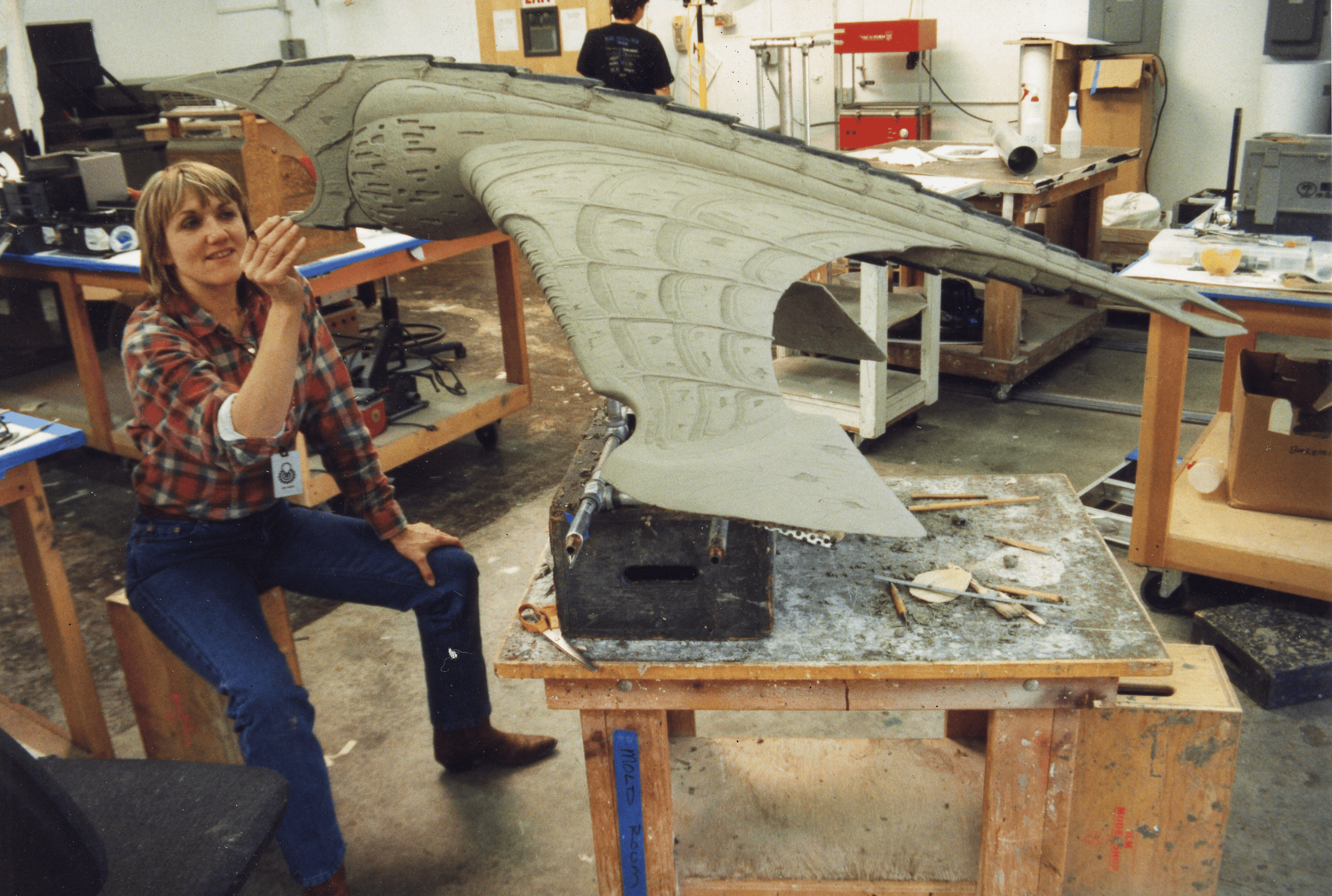

Without a doubt, the Enterprise-E. We came up against many issues building it. There were a couple of missteps along the way which cost us time… such is the way. We were up three days straight trying to finish it for the movie poster. The company that would be producing the model kit would also be using these photos. After we got it finished enough for the photos, we went home and slept.

When decisions were being made about which department would make the model, the CG department or the model shop, it became a bigger and bigger point of anxiety for all of us. Digital models were becoming better. The future of the model shop seemed very insecure, and I decided to move to CG for Star Wars Episode III. I figured it would be the last time I might be invited to make this leap (I had turned it down once before), and I took it. It was a very good decision.

You are so smart! Yes, I worked for three companies in between ILM and Tippett Studios and did expand my skills a bit at each place. I left ILM when Doug Chiang, a long-time and great colleague, invited me to come work at ImageMovers Digital, where I spent about three years until the company disbanded. I then went to Digital Domain San Francisco until that office was shut down, then CamD (Creature Art and Mechanics Digital), where I began to learn hair on top of my paint responsibilities until company finances became a problem. I finally landed at Tippett where texture painters are expected to do look-development and hair, so that was where I really pushed my own envelope in the digital world.

Though I didn’t feel like I learned some the software quite as fast as the younger people, I was always made to feel that my practical skills were of great value to them.

They listened and my observations were considered. That is one of the many things I appreciated about Tippett… that they put importance on people who “made things” in the real world. One of the pitfalls of CGI is that it can be noodled forever, but in dailies, Phil would often cut the dithering and say “Done!”. Tippett is a company of great loyalty to the employees.

I worked on paint for the Rodger Young and on the Ticonderoga, possibly other of the smaller scale ships, at ILM. I also did stage support for it. They were very long shooting days, which is what I remember most.

Tippett Studios was doing creature work for the movie at the same time as we were doing 911s (helping out another company) on the hard-surface models, so the two companies got together for the screening.

Yes. Though CG models have vastly improved, I often have a bone to pick with CG lighting. If physical models were being used, lighting would be more natural, but I find that CG lighting often gives away even very good digital miniatures. Overall, CGI still feels stark to me compared to physical models.

It makes all of us who regularly worked in the “Golden Age” feel like rock stars! There is a lot of nostalgia in looking at photos of those times and revisiting the models in the real world, which I periodically get to do. Seeing my babies come up for auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars is pretty stunning. Knowing that my work is being valued in this way is very satisfying.

The teamwork in the model shop and the rest of ILM created a family that to this day sticks together through thick and thin and participates in each other’s joys and sorrows.

There might be specific projects that would tempt me, but I would not return indefinitely. Glamorous and fun projects come up periodically. But it’s hard to take me away from my own studio, these days.

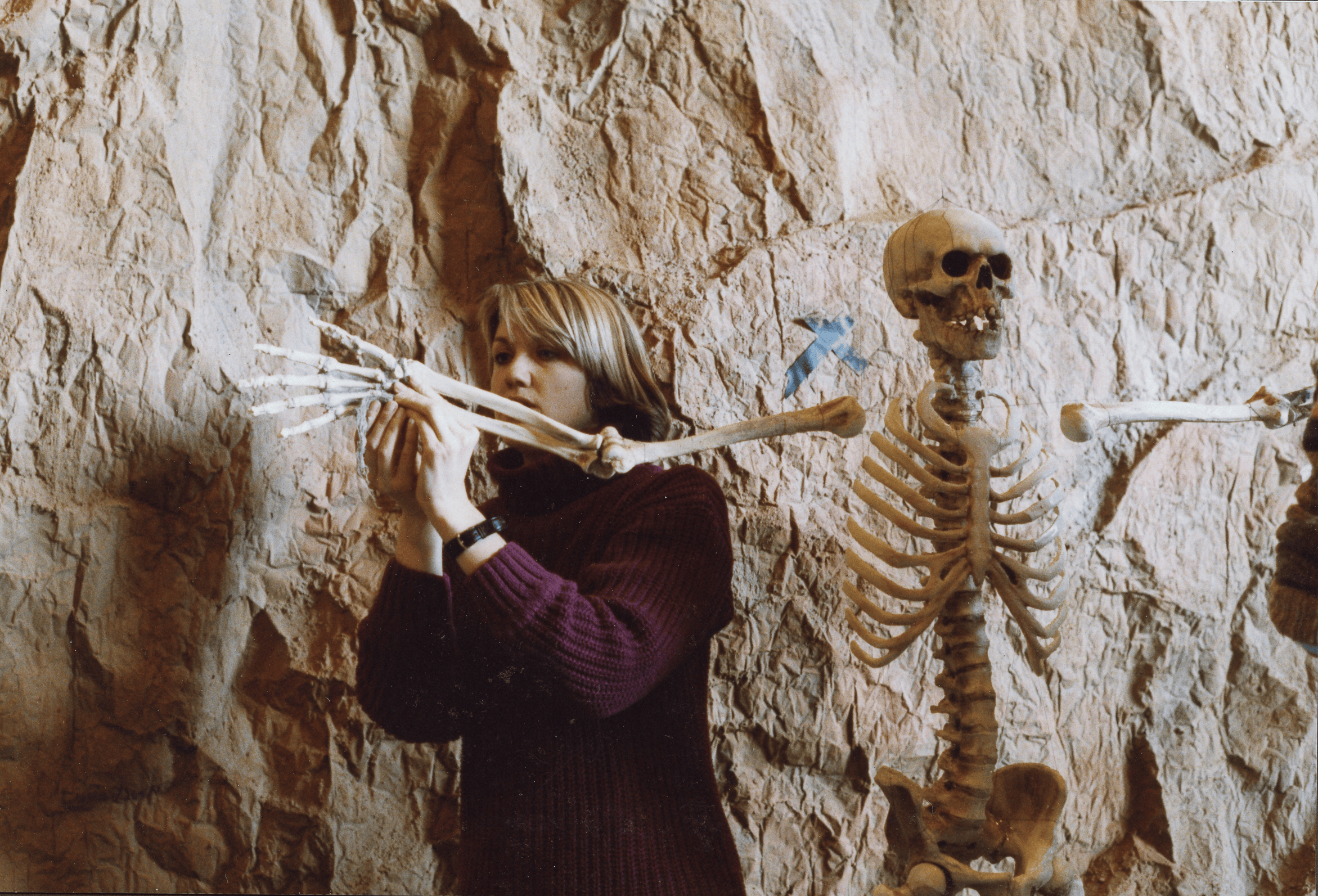

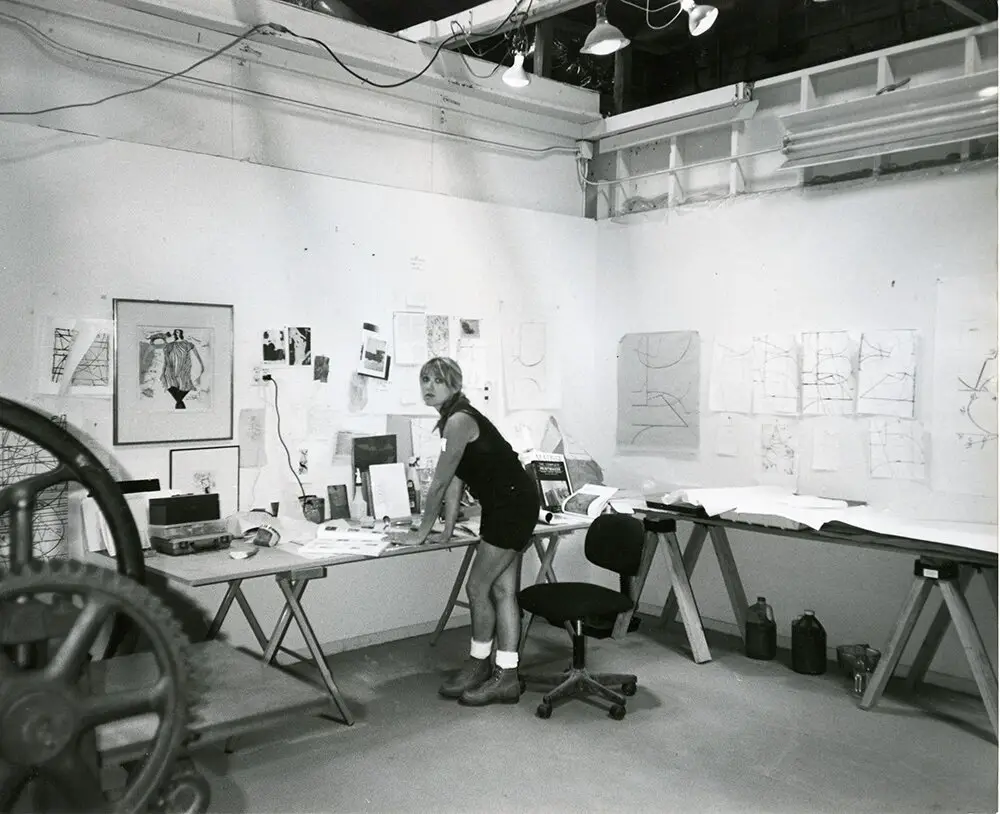

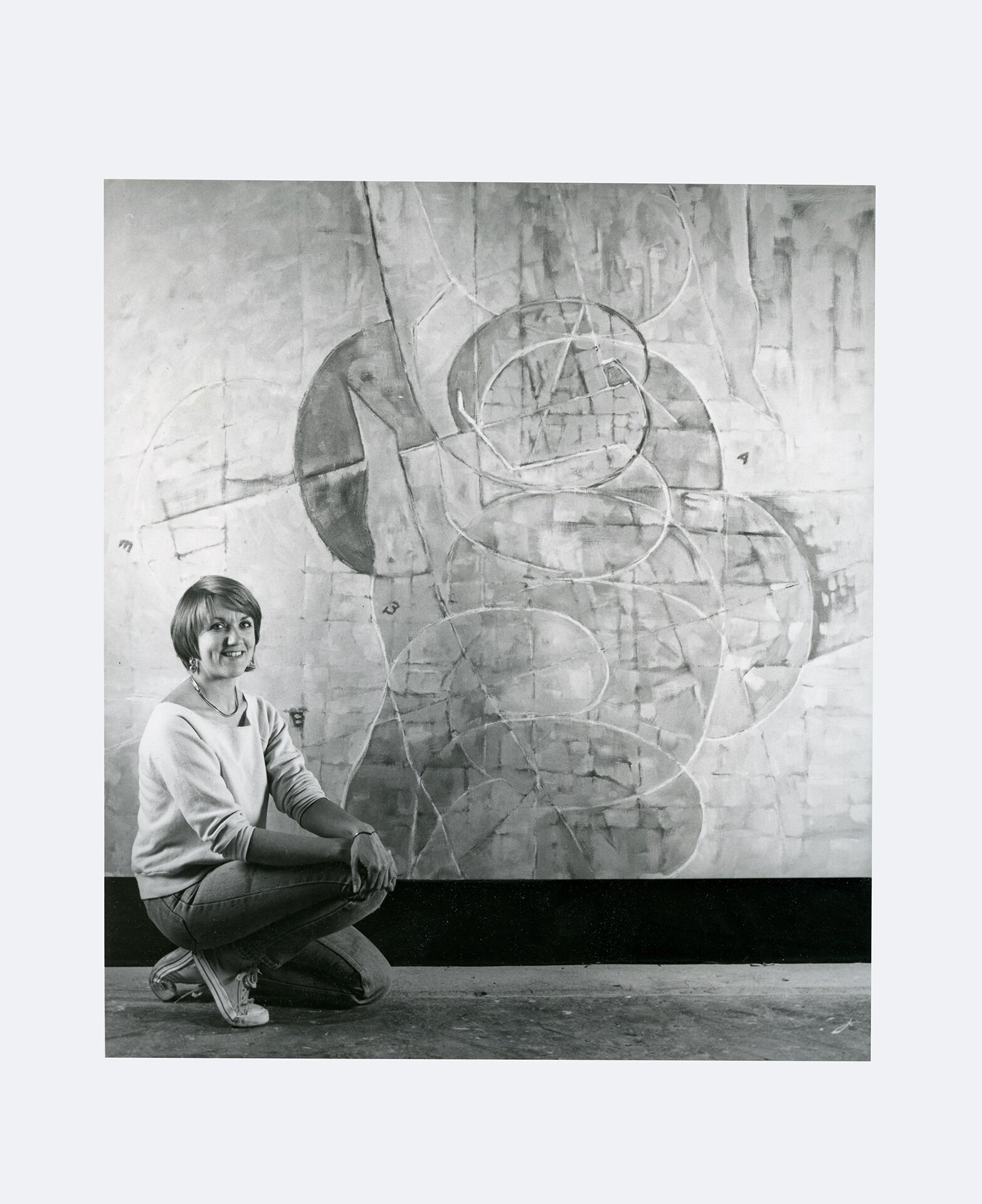

Photos of Kim’s Work

Shots From Behind the Scenes of Star Wars

Shots From Behind the Scenes of Star Trek

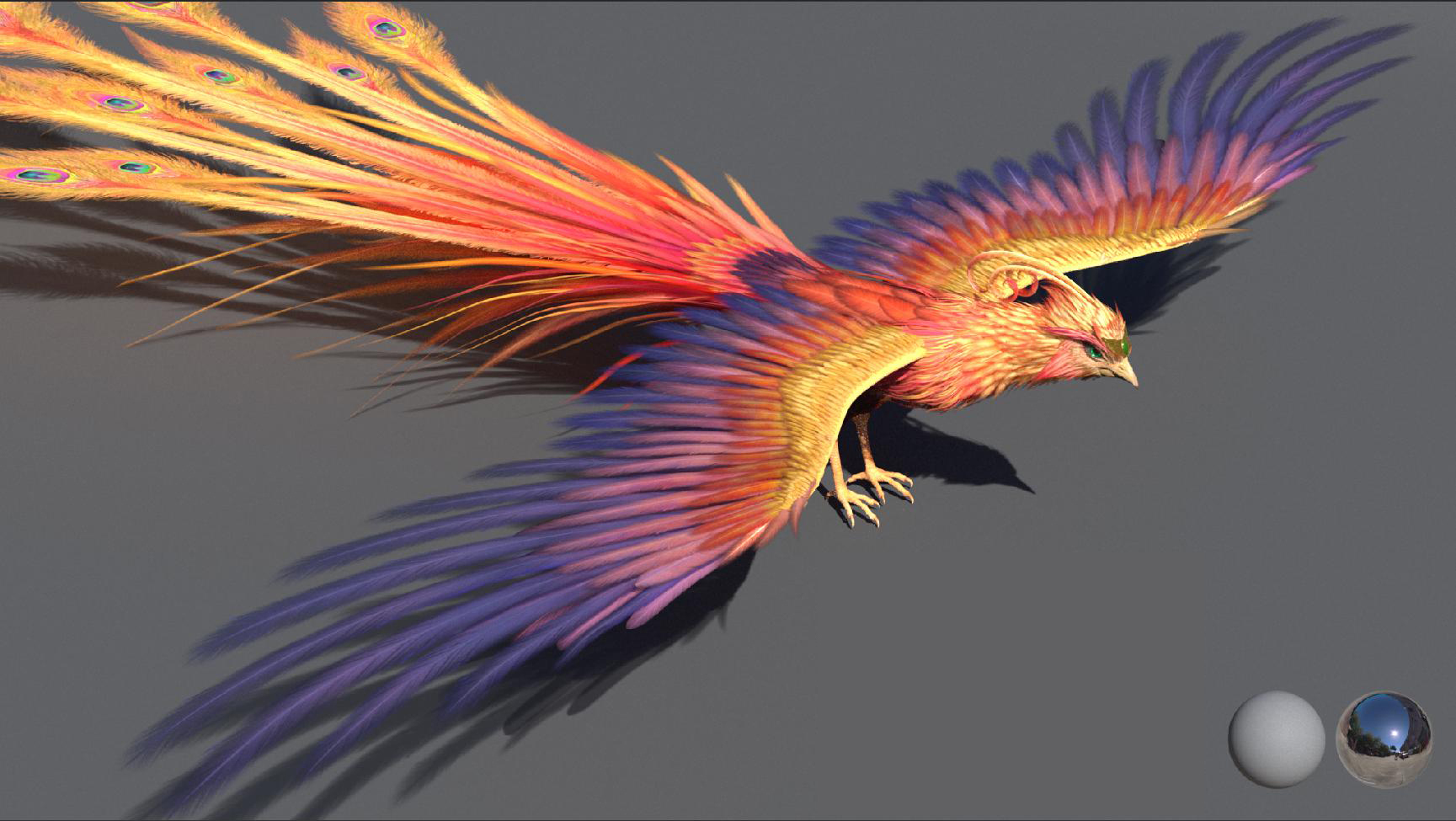

CGI Lookdev Assets

You can find Kim Smith at: LinkedIn and Kim Smith Studio.