Table of Contents

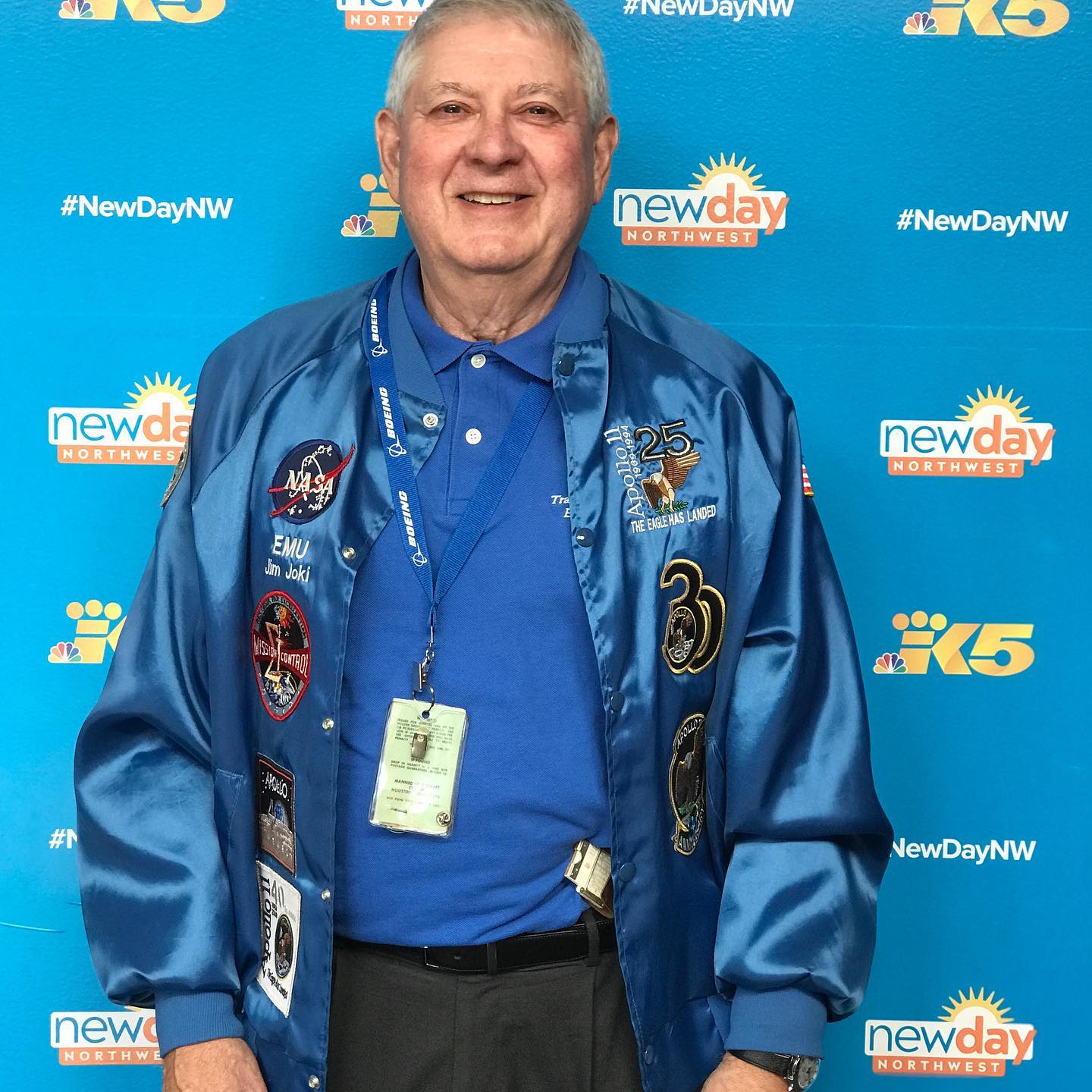

In May 2024, we had the opportunity to conduct an interview with James Allen Joki, a NASA engineer who contributed significantly to the Apollo missions and later transitioned to a successful career in medicine. This interview provides insights into his dual careers and his thoughts on the intersection of technology and medicine.

About James Allen Joki

James Allen Joki was born on August 14, 1942, in Seattle, Washington. He graduated from Ballard High School in 1960 and earned a degree in aeronautical and astronautical engineering from the University of Washington in 1965. Joki joined NASA and became a flight controller responsible for the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) during the Apollo missions. His work was crucial in ensuring the success of the first manned moon landing.

After the Apollo program, Joki pursued further education, earning a Master’s degree in Physiology and a Doctor of Medicine degree. He specialized in obstetrics and gynecology, integrating his knowledge of telemetry from space missions with fetal monitoring. Joki had a distinguished medical career and was also an active community member, particularly with the Boy Scouts of America.

Recommended Reading

The Right Stuff by Tom Wolfe is an insightful narrative into the lives of the first American astronauts and their groundbreaking achievements. The book delves into the personal and professional challenges faced by these pioneers, offering a detailed look at the early days of the American space program.

James Allen Joki Interview

1. Agena: A series of rocket upper stages developed by Lockheed, used as a target vehicle for the Gemini manned space missions. ↩

2. Lunar Module: The spacecraft that carried astronauts from the command module to the lunar surface and back. ↩

3. ECS (Environmental Control Systems): Systems responsible for maintaining a stable and life-supporting environment within the spacecraft. ↩

4. Space Shuttle Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU): A spacesuit that provides environmental protection, mobility, life support, and communications for astronauts performing extravehicular activity (EVA) outside the spacecraft. ↩

5. Neil Armstrong: An American astronaut who was the first person to walk on the Moon. ↩

6. Buzz Aldrin: An American astronaut who was the second person to walk on the Moon. ↩

7. EVA (Extravehicular Activity): Any activity done by an astronaut outside a spacecraft beyond the Earth’s appreciable atmosphere. ↩

8. Apollo 9: A mission to test the lunar module in Earth orbit, which included the first manned flight of the module. ↩

9. Rusty Schweickart: An American astronaut who flew on the Apollo 9 mission and conducted an EVA to test the lunar module. ↩

10. Apollo 8: The first crewed spacecraft to leave Earth orbit, reach the Earth’s Moon, orbit it and return safely to Earth. ↩

11. Gene Kranz: A NASA Flight Director and manager, known for his role in directing the successful Mission Control team efforts to save the crew of Apollo 13. ↩

12. Ken Mattingly: An astronaut who was originally assigned to the Apollo 13 mission but was replaced due to exposure to German measles; he later flew on Apollo 16. ↩

After the initial interview via mail correspondence, we followed up with Mr. Joki to continue the conversation over the phone.

Phone Interview

James Allen Joki: The Agena was the target booster for the Gemini missions. I was in that bridge, and the whole purpose was to learn radio communications, voice discipline, and all that. We started to learn about the systems and what information we needed to troubleshoot them. From the Agena, I went right into the lunar module. My best friend, who was my superior for about a week and later retired from NASA, was working on the environmental controls of the lunar module. We both worked on it together. That’s when I realized that the spacesuit interfaces with everything, and nobody was looking at it from mission control because they were all focused on Gemini. So, everything that I needed to know was just across campus in the crew systems division, and I volunteered to be a test subject.

James Allen Joki: I got more and more involved, and I was the same size as John Young, so I got to test all his spacesuits, backpacks, everything. I became an expert in that area. I was looking at all this and said, “Golly, these radios are the same thing I used as a kid, you know, push-to-talk CBs,” and said, “Man, with the time delay, the round trip of 2.4 seconds, nobody’s going to be able to talk to anybody. Everybody’s pushing a button.” So, I walked over to the Engineering division next door and said, “We need to do something better.” And they said, “Yeah, you’re right. The radio communication was AM, and we need to go to FM.” The data was terrible. I tried to get more transducers, and they finally did get a CO2 transducer. I fought for that, so you knew that the CO2 wasn’t building up like in the lunar module. You see the movie Apollo 13, and you can see they did have a gauge set of CO2. We didn’t have one on the backpack. I wanted one, but they weren’t ready.

James Allen Joki: A lot of our consumables had to be calculated. We had what’s called an Olivetti, which was sort of a programmable device with a memory disk card you put through, which had all of the calculations you wanted. Then you put in your raw data and information amounts. So, even though they had the big computer center, it was worthless from our point of view because they never worked in real time. So, it was all the stuff you need. It was great for the people trying to figure out how to get to the moon. In fact, it didn’t help us in real time. It was interesting to get other divisions to work with us to get us the units. Throughout Apollo, they made a few corrections, but by the time we got through with it, the basic unit was good.

James Allen Joki: It was always fun to have to sell the pitch on the radios, not being an electrical engineer, to Chris Kraft and all those guys. They had their meeting on Fridays at 9 or 10 o’clock. Then I’d get a call from my branch chief saying I needed to talk to my branch chief, who needed to talk to the division chief, who was Krantz. And he said, “Who wants to talk to you? The flight office director, which was Krantz.” He said, “Okay, what is this all about?” “Well, your memo about the radios.” “Oh, okay.” So, as a stupid aeronautical engineer, I was trying to explain all the electronics and all that. Most of them are engineers in a certain fashion, so they understood it. That was about a $10 million investment, but we got decent radios and data. That was a place for that experience. It’s funny, you get into a system, tear it apart, and figure out what needs to be improved. That was part of the problem with the old lunar module being late on a lot of things because people kept trying to change what it was supposed to do.

James Allen Joki: The command and service module, the first one, they started early. They were confronted with all the electronic and thermal isolation problems that resulted in the Apollo 1 fire because Gus Grissom said all the time, “It’s a lemon.” And we were trying to beat Kennedy’s proclamation to get there before the decade was over, and we learned from a lot of things. Same with Challenger. You know, you got to look at the engineering aspect and forget about the management. That’s how we lose astronauts and that sort of thing. But it was a really exciting time, you know, as a young engineer. My very first mission was Apollo 9. The whole thing was put together, the lunar module, the command module, the EMU, and Rusty Schweickart, who was a good friend, was going to be the astronaut who was going to do all that stuff. So, he and Ken Mattingly, who I find surprising, never ever used the EMU. But these are smart guys, pilots and all. We’d be going through all the system briefs and malfunction front, what parameters we need to know to continue on, and what they could do if we lost ground communication with them. There were some great conversations and all, but I remember Rusty got motion sickness.

Tim Santens: Mm-Hmm.

James Allen Joki: And they cut the air-to-ground and went to a private line. I’m on console. My very first time on console. You know, spending three years to become a flight controller. My very first mission, you’re going to have a two-and-a-half-hour EVA with all the equipment, looking at the data and being able to monitor systems and all that. It wasn’t the same as on the lunar mission because in those days, you only had about eight or nine minutes of data as they went over various sites because you’re in Earth orbit. Well, now they’ve got the capability of continuous communications because of all the satellites. So, you have to look at the data in eight minutes, make a decision to the flight director who would make the decision to the Capcom, or communicator, to make the announcement.

James Allen Joki: Anyway, I was all ready for it. And all I heard is that all of a sudden air-to-ground is going to secret or whatever they call it, confidential, which left me out. And I’m the flight controller for their backpack. And it was that Rusty was just throwing up his cookies, and he’s a pilot. We found this out later on the shuttle program. They never did any EVAs until about two days to let their vestibular system, the middle ear, start working. Frank Borman, a pilot, and Lovell always talked about how Frank Borman threw up all the way to the moon on Apollo 8 and all the way back because he could never get his middle ear to stabilize. But anyway, they said that due to circumstances they never told us about, Rusty was going to go out, put his feet in the golden slippers, and turn everything on so I could look at the data. I had about eight minutes to make sure that the telemetry was working, check the backpack out, and gather data.

James Allen Joki: Rusty went out, carefully put his feet in the slippers, communicated with the command and service module, which was docked at the time, talked to Scott, talked to me, and talked to the ground. Next thing I know, he’s back inside, and it’s over. It was interesting not knowing what was going on. We found out later at the debrief, and that’s why he never flew again. Nicest guy, great pilot, great engineer, but we didn’t realize that some people are so sensitive to space initially, and the middle ear gives them trouble.

James Allen Joki: The real mission was Apollo 10. They went to the moon with everything, but they weren’t going to land because there were too many variables. We heard they didn’t give them enough fuel, but that’s not true. They didn’t shortcut the fuel. They just wanted to check all the programs out. It was going to be a dry run, going down to about 30,000 feet where they would do the final descent engine burn. We just watched that one. The backpacks were never used. Then came Apollo 11 with Neil, who was probably the smartest and nicest guy to work with. Buzz Aldrin, on the other hand, was a PhD and a bit of an asshole. Nobody liked him. He kept telling everyone that he should be the first one out and that the commander should stay on board in case of an emergency. Neil, being the gentleman he was, didn’t say a word, but it went all the way up to the top brass. They decided Neil would be first.

James Allen Joki: Neil was a true engineer. Even during the briefing, people would ask emotional questions, and he would respond with technical details. He was not the kind of guy to get excited. He said he could deal with Buzz. In an interview, when asked how he and Buzz got along, he said, “We were compatriots, but probably not the best of friends.” Buzz took credit for things he didn’t need to, like breaking off the switch on the lunar module. His backpack broke off one of the toggle switches. They didn’t tell us until just before launch, and he used his pen to push it in. The engine guys said there was the same switch on Neil’s side, so it wasn’t a big deal. The real worry was what if the engine didn’t shut down when they were getting ready to dock. It wasn’t about getting started; it was about shutting it down.

James Allen Joki: During the landing, Neil went through the checklist like a good pilot, and then said, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” He did all the engineering stuff first. There are a lot of good stories, and they come out every once in a while.

Tim Santens: When you say you would get the data back, how did you receive it? Did it show up on the screen or was it a printout?

James Allen Joki: Oh, yeah, both. We had CRTs, which are the old TV screens. The telemetry was sent in real time, just delayed by 1.2 seconds. I had about eight or nine, maybe 12 parameters plus calculations coming on the screen. I had one screen for Neil’s EMU and one for Aldrin’s. I was looking at pressurization, oxygen levels, temperatures, cooling, and so on. The temperatures had to be calculated for the cooling, which was called a liquid cooling garment. The sublimator eliminated the heat, and they could control that by a diverter valve. The flight director asked me twice about the differences in cooling modes between Neil and Buzz. I explained that Buzz was working harder and had his cooling mode set differently. That was it. The flight director also asked about consumables, and I confirmed they were nominal.

James Allen Joki: During Apollo 11, we monitored everything carefully. The backpacks were designed for eight hours, but the first EVA was only 2 hours and 34 minutes. It was tense making sure everything worked. After the EVA, all my backpacks were left on the moon. They were rechargeable, but weight limitations meant they were discarded to make room for lunar samples. It would have been nice to get one back, but they prioritized rocks over my backpacks.

Tim Santens: That must have been interesting.

James Allen Joki: Yeah, it was. The moon is littered with stuff we left behind. It will be there for millions of years. I don’t know how long the seals will last. They go from minus 250 to plus 250 degrees and get radiation. Eventually, the rubberized seals will fail, and the oxygen will leak out. It would be interesting to see the old equipment again.

James Allen Joki: During Apollo 12, they landed within 100 meters of the Surveyor that was sent out four years earlier. They brought back parts of it. It showed how accurate they could get with the big computers. In mission control, I was just watching my data while everyone else watched the TV screen. It was a terrific, fun program.

James Allen Joki: I keep in contact with my buddies. Most of them are retired. I’m going down in July with my grandsons to go through the reunion and take them through mission control, show them where I used to sit. We used to have about 60 people in our branch; now we’re down to about 10. Old age catches up with us all.

Tim Santens: Yeah, happens to us all.

James Allen Joki: How did you get my name? I’ve been getting a lot of letters. I imagine someone posted my address after writing to me. I’ve received quite a few letters and try to answer them. I don’t have a lot of pictures left because my grandkids want them all. The people who send pictures, that works really well. I try to sign those and not screw them up too badly. You had a lot of questions, but they were good. I figured you were around 22 when we landed a guy on the moon. The average age of the engineers in mission control was 26. I always think about that. How many 26-year-olds would you trust with putting people on the moon? It was really exciting, and we always had a big splashdown party afterwards. I didn’t really understand what it was about at first, but it was a big celebration.

James Allen Joki: The only mission we never had a splashdown party for was Apollo 11 because they were put in isolation and then sent around the world. It wasn’t until the 10th anniversary that we had a proper celebration with them. My kids were old enough by then to appreciate it. It’s funny to look back at some of this stuff. My daughters cut in line in front of Neil Armstrong at the picnic, not realizing who he was. We got pictures of them with Buzz and Neil. It’s funny to look at some of this stuff.

Tim Santens: That’s interesting.

James Allen Joki: There was a movie called Marooned that came out before Apollo 12. Richard Crenna was in it. It was about an astronaut who went berserk and died. They were going to premiere it on campus at our big auditorium, but the big honchos said no because an astronaut died in the movie. They moved the premiere to a local theater. They got high school seniors dressed up in tuxedos, and the first three rows were reserved for the movie stars and astronauts. But the teenagers didn’t know who the astronauts were and wouldn’t let them sit in the reserved rows. It was typical of a NASA thing, not informing people who was really supposed to sit there. The movie wasn’t all that good, but it was interesting because Apollo 13 had similar elements with a hurricane affecting the recovery area.

Tim Santens: That’s dramatic.

James Allen Joki: Yeah, if you can find the movie, it’s interesting. It was just before Apollo 12, so they didn’t want to show it on campus because an astronaut dies in the movie. It’s funny to think about that now. There’s renewed interest in going back to the moon.

Tim Santens: Yeah, it’s interesting to see the renewed interest.

James Allen Joki: It’s like Boeing. They’re over cost and delayed. NASA is paying for the Starliner, but Elon Musk is paying for his own projects. My son, who is a pilot, said that’s the way to do it. You just keep building and flying them. If one blows up, you figure out why and fix it. Since it’s his money, he can afford to take risks. NASA has to be more cautious.

Tim Santens: That makes sense.

James Allen Joki: It’s complicated. My grandson tells me about all the programs and engines. They’re using the old shuttle engine upgraded to 500,000 pounds of thrust. It’s hard to keep up with it all. Back in our day, I just kept up with our program, and that was enough. Now there are so many different vehicles and programs.

Tim Santens: Speaking of technology, what was it like to have access to computers when the general public didn’t?

James Allen Joki: We had punch cards and IBM machines. In my last year of college, we had to punch cards to run programs. I could never get one to work because of hanging chads or misaligned cards. The guys coming in after me were mathematicians, and they handled the programming. We had a whole division, MCATS, Math, and Computer Help or something like that. We gave them the information, and they did the programming. But we found that kind of information wasn’t realistic enough for real-time operations during missions.

James Allen Joki: So, we got this little Olivetti machine with a magnetic tape. It had all our calculations, and we could input raw data. The propulsion guys used it to figure out how much fuel we had left. There wasn’t a real fuel gauge; they went by temperature, pressure, and thrust. The power guy thought we had about a minute and 30 seconds of fuel left, while everyone else thought we had 45 seconds. I wasn’t going to correct anyone. The flight director said 45 seconds, so we had 45 seconds. But we did have callouts like “one minute” and “30 seconds” to abort if needed.

James Allen Joki: That little machine was essential. One time, they were moving it across the parking lot in a shopping cart, and it fell out and shattered. We had to scramble to find another one. We borrowed one from the engineering division. It stayed in mission control after that. It had all our calculations for consumables like oxygen, water, CO2, and power.

Tim Santens: That’s crazy. Now we have so much more computing power in small devices.

James Allen Joki: Yeah, it’s amazing. If you have the telemetry data and sensors, modern devices can do a lot. Back then, we struggled to get additional sensors. They didn’t have the money, or the sensors were too big. They always called me on Fridays about removing weight from the spacecraft. If the contractor could remove weight, they got money.

James Allen Joki: One time, they wanted to take fluorescent discs off the command module around the door and handholds. The contractor thought they were unnecessary. I explained that if the astronauts had to cross to the other vehicle in the dark, they needed to see the handles. The engineer didn’t research why they were there. We had a mission rule for formation flying, where the command and lunar module would fly close, and they could cross over if needed. That made life interesting.

Tim Santens: It’s interesting to see how things have changed.

James Allen Joki: Yeah, SpaceX has a similar philosophy of stripping down to the bare minimum. It’s scary sometimes. Redundancy is important. I’m curious to see more about their suits. They’re not considered EVA suits. The suits we used in the International Space Station were never designed for walking on the moon. They’re hard torso suits that lock into footrests or the Canadian arm. They were never meant to bend. Our original suits had a zipper that went from the front crotch to the back, but you couldn’t sit down. Later, they made the zipper go diagonal with O-rings so you could bend.

James Allen Joki: The new suits have to be redeveloped for lunar missions. We’ll see what happens. Technology gets lost over time. One of the recent summaries was about the movie The Martian. The guy who wrote the book did a lot of research. The spandex suit idea makes sense, providing pressure against the body and the suit. It keeps you above the triple point so you don’t have to worry about sublimation. You still need a helmet for oxygen and protection, but it’s a well-done concept.

Tim Santens: It’s interesting to see how technology and ideas evolve.

James Allen Joki: Yeah, it’s fascinating. I always enjoy going back and talking to the guys. We visit the new mission control room. One time, a current flight director told us not to bother the people on console. But we all scattered and went to our respective consoles. A young woman was on the EVA console, and I told her about some of the problems we faced. She said, “I wasn’t even born then.” It shows how much information gets lost over time.

Tim Santens: It’s a shame there was such a lack of continuity in the space program.

James Allen Joki: It was a political decision. Programs were shut down, and contractors lost their engineering staff. Now we’re trying to go back to the moon by 2025, but we lost a lot of knowledge. It’s good that SpaceX is around and willing to invest their own money. Their suits are different too. They have a connector in the armrests, but I’m not sure if they have a liquid cooling garment. It’s interesting to see how they’re approaching it.

Tim Santens: It must have been amazing to be part of such groundbreaking work.

James Allen Joki: It was. Back in our day, we just kept up with our program, and that was enough. Now there are so many different vehicles and programs. It’s hard to keep up. But it was an exciting time, and I’m proud to have been part of it.

Tim Santens: Mr. Joki, it was really nice talking to you. Thank you so much for sharing your stories and answering my questions.

James Allen Joki: I don’t mind doing that. I usually throw a card in if someone wants to chat. If I’m not busy, I try to share some stories. Okay, you take care. Have a good day.