Table of Contents

Introduction

In September 2024, I had the privilege of sitting down with Steve Ritchie, a legend in the world of pinball design. Known for his fast-paced, high-energy games, Ritchie has earned the nickname The King of Pinball throughout his decades-long career. From his early days designing groundbreaking machines like Flash and Firepower to more recent successes like AC/DC and Star Trek, Ritchie’s work has captivated generations of pinball players.

In this exclusive interview, Steve shares insights into his creative process, the evolution of pinball technology, and what it takes to create an unforgettable game experience.

About Steve Ritchie

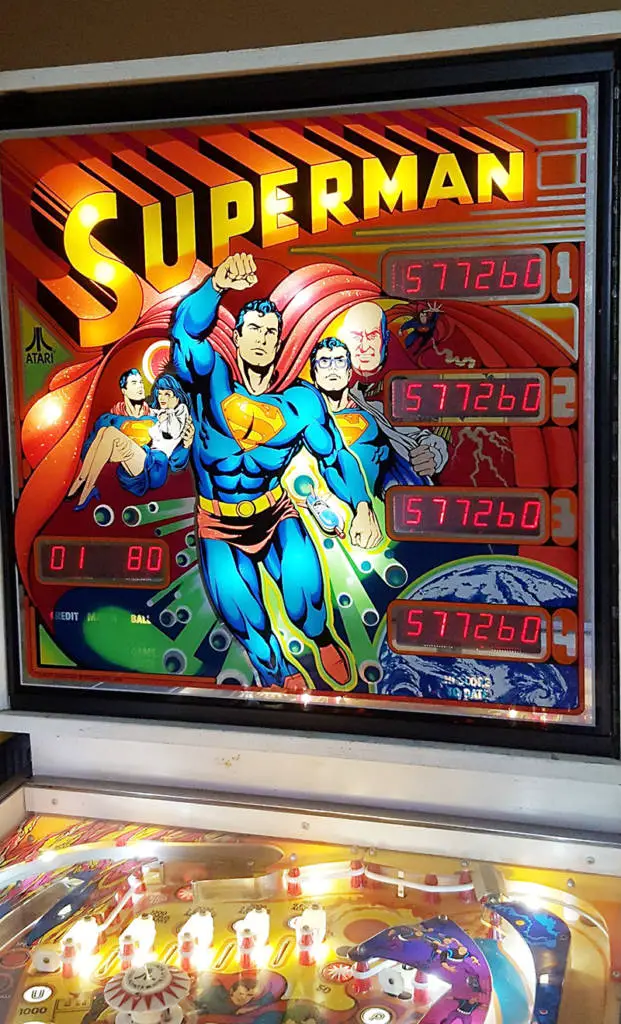

Steve Ritchie is widely considered one of the most influential pinball designers of all time. He began his career in the 1970s, working for Atari, where he designed games like Airborne Avenger and Superman. However, it was at Williams Electronics that Ritchie truly made a name for himself with his design of Flash in 1979, which introduced innovations such as electronic sounds and the first-ever pinball game with a multi-level playfield.

Ritchie’s career includes designing some of the best-selling and most beloved pinball machines in history, including Black Knight, High Speed, Terminator 2, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. Known for his “flow” designs—where the ball moves rapidly and smoothly around the table—Ritchie has continually pushed the boundaries of pinball game design.

Ritchie’s recent move to Jersey Jack Pinball marks a new chapter in his storied career, and fans eagerly anticipate what he’ll create next. As a mentor to many and an innovator in the industry, Steve Ritchie remains a pivotal figure in the ongoing evolution of pinball.

A Conversation with Steve Ritchie

Beginning a Career at Atari

Tim Santens: There’s three lines of questioning that I had wanted to touch on with you, including early days at Atari, Mortal Kombat and your broader pinball career.

Steve Ritchie: Well, I started working at Atari in 1974. I think I was employee number 50.

I worked at making universal test fixtures for all the games they had to date with huge burn-in ovens for cooking boards overnight. PC boards with all the power running. There would be heavy fallout [1] the next day. We’d bring the boards to the table and these ladies would remove chips and replace them until they worked.

I did that for about a year. Then an officer of the company came and asked me if I wanted to be part of a pinball division [2] . And I said sure. I started working with this guy they hired from Chicago. He taught me how to lay out a game, what a drawing looks like, and how to put them together. After about a couple of months of that, I thought, “Hey, I can do this.” So I grabbed a big piece of wood—they were all wide-body pinball machines in those days. I taped a piece of paper to it and started drawing a game. I worked on it for six months at home, then brought it to my boss.

I showed it to him, and he said, “You don’t have a degree in industrial design, so you can’t be a game designer.” I thought, I don’t think I have to have a degree in industrial design. I played pinball. I understand it. So I brought it to Nolan Bushnell and showed him. And he said, “You did this at home?”

“Those were his exact words: ‘Poof, you’re a designer.’”

I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You want to be a designer?” I said, “Yeah.” Then he said, “Poof, you’re a designer.” Those were his exact words. Two days later, I had a big drafting table, 8 feet long by 4 feet high, and a Muto drafting machine. Everything was hand-drawn in those days. So I started drawing my game.

Designing Pinball Games

Photo credit: Dennis Kriesel via Pinball News

Steve Ritchie: I made it happen, and they produced it. It was called Airborne Avenger [3] . But it was the handiwork of a clueless guy who didn’t know what he was doing. We sold quite a few—around 500 or so. Then they said we’ll start on the next game. And the next game was going to be a contest between me and Gary Slater [4] —the only other game designer they had—for the rights to use the Superman license. I wanted it bad. So I made a game and it took me like four whitewoods—prototype pinball machines with no screen, just white maple. We coat it with varnish and play the game. Anyway, I won the contest and got to make Superman.

Transition to Williams

Steve Ritchie: Shortly after that, I got an offer to go to Williams. I was totally excited. They needed me. They needed us—Eugene Jarvis [5] and me. He was a really great programmer. He owns a company called Raw Thrills and Play Mechanics now. He was a super imaginative guy, and we had a great time at Williams. He didn’t come right away. I went to Williams immediately and made a game that sold 19,000 machines—a little more than that. It’s the most I ever sold of any game.

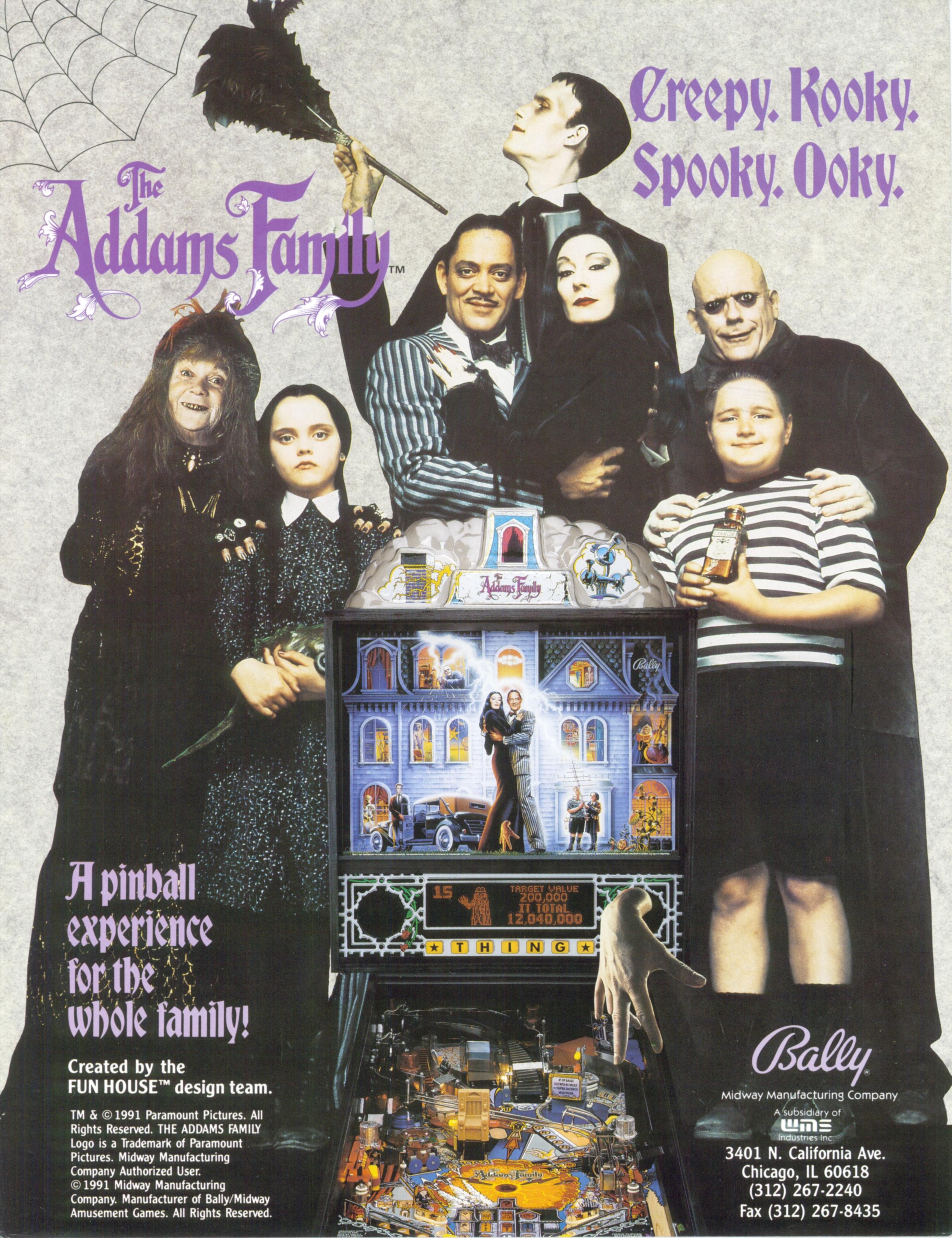

I went to the sales guy and said, “Can we sell a few more so we can break 20,000?” And he said, “Nah, we want to leave the market wanting.” So that’s okay. Anyway, it held the production record until The Addams Family came out, which became the largest-selling pinball machine of all time, done by Larry DeMar and Pat Lawlor.

Firepower

“Firepower was the first solid-state multi-ball pinball game. Firepower was a smart game.”

Steve Ritchie: The next game was Firepower. It was the first solid-state multi-ball pinball game. There were others, but they weren’t smart. Firepower was a smart game. And that’s the first time I did speech in any game. We had like 11 seconds of speech time, so I had to say everything in a monotone—like “fire,” “power,” “you are destroyed”—so we could reassemble the words to make different phrases.

It’s kind of crude, but it was the first game with speech. However, it didn’t get to the outside world first because we made Gorgar shortly after that. The president said, “You can be the second game with speech. We’re going to stick Gorgar out there.” It did pretty well.

Anyway, I made a lot of games for Williams—18 or so, I think. Plus, I made slot machines and redemption games.

Williams/Atari Merger

Steve Ritchie: Around 1996, we weren’t selling pinball at all. The boss wanted to build slot machines because there was a lot more money in slot machines. Eventually, they phased it out, but I didn’t wait. I decided I wanted to go back home to California. So, I took two weeks of vacation and went out there to look for work. I ran into Atari—the new Atari—and I was ready to take a job there.

“We bought Atari yesterday. That was nice. I didn’t have to negotiate anything.”

We hadn’t discussed everything, and it wasn’t finalized. Anyway, when I got back from vacation, the president of Williams called me up and said, “Come up to my office.” So I did. He said, “You’ve been looking for work.” I replied, “Yeah, well you guys kind of forgot about my contract.” Then he said, “Well, I gotta tell you we bought Atari yesterday.” [6]

That was nice. I didn’t have to negotiate anything. They gave me the same money I was making, plus a raise, and said, “Go do it. You’re going to produce video games.” So, I produced a couple of games. One was California Speed—a father-son-daughter driving game. It was kind of easy, like Cruisin’ USA. [7]

Steve Ritchie: You could tell by the blue seats. That sold about $60 million worth. Then I started on a second game called Mean Streak. In 2000, with about 18 months into the game—it takes about two years to develop a game like that—we found out that Williams was going to close Atari, close Midway, and close everything.

So they paid off my contract, and I went home. I designed a slot machine called The Vault, and it was stolen from me by IGT (International Game Technology). [8] They have a hundred lawyers. You’re never going to win any kind of legal battle in Nevada. The state of Nevada receives so much revenue from slot machines. So I just gave up.

Stern Pinball Inc.

Steve Ritchie: After that, Gary Stern [9] called me and asked, “Do you want to come to work?” I said, “Sure.” He said, “You can work in California if you want.” I replied, “How about part-time in California and part-time out there?” He said, “Sure.” So for six years, I was commuting, and I loved it.

I could go back to California, work, and also ride my dirt bike. It took me 15 minutes to get to the mountains. Riding is a mad passion of mine. I still want to do it, but I’m 74 now.

Anyway, Stern Pinball almost went out of business. Then, [Dave Peterson] [10] came in, and he was way better with finances, and a really good guy. They called me back. My partner Lyman Sheats and I made AC/DC and Spider-Man. [11]

“I made Led Zeppelin pinball, but they didn’t buy ‘Stairway to Heaven.’”

I think I did eight or nine or ten games there. I’m not sure. Anyway, they got cheap with parts. The bill of materials for their pro model game was so strict that it was hard. I made Led Zeppelin pinball, but they didn’t buy “Stairway to Heaven.”

I couldn’t believe they didn’t do that. I mean, it would have cost four times more than the other songs, but I said, “Get rid of four, and I’ll take that one.” They never got it. I ended up with two songs I absolutely hate that somebody else picked. Whenever I do a music game, I look at Billboard, Rolling Stone, and all the sales data to pick the best songs.

Jersey Jack Pinball

Steve Ritchie: After that, I decided to go to work for Jersey Jack Pinball. They gave me a great offer, and that’s where I am today.

Steve Jobs and Woz at Atari

Tim Santens: 1974, the year you were hired at Atari, was the same year that Apple’s Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were hired there as well. Did you have any interaction with them?

Steve Ritchie: Oh yeah, they worked like 25 feet from my cube.

“Steve Wozniak was a great guy. Steve Jobs was an asshole. He stunk. He never took showers.”

Steve Wozniak was a great guy. Steve Jobs was an asshole. From the first moment. I mean, I would say good morning to him, he would say nothing. And if you got close to him, he stunk. He smelled awful. He never took showers. The classic picture of him leaning back in the chair with his feet up on the desk while Steve Wozniak does everything.

That’s how it was. He was just a bum with some ideas, but then I found out the game that they were working on was already designed by a vice president there. It was Breakout. It was a good game, a great game actually, and he took all the credit for it, but he wasn’t really the designer.

Anyway, they fired him once for smelling bad, then they kept him for a while, and then finally he left.

And, you know, I just have no use for the guy. I have never purchased any Apple products. I never will. I just don’t want to. I don’t care. I mean, he was bad to his wife, to his daughter, everyone around him. I mean, have you read any books about him?

Tim Santens: Yeah, I’ve definitely heard about what he did, his interactions with his daughter and how she was estranged.

Steve Ritchie: It’s not just that, the people that worked for him, like he gathered a Macintosh team and another team working on the next product, I don’t know what it was. He’d get up in front on the stage in this big auditorium and he would say, ‘Okay guys, you that did the Macintosh, you’re the B team. This is the new A team. And by the way, all B’s are fired. Thank you.”

Tim Santens: Yeah, he was definitely a slave driver and an asshole for sure.

Steve Ritchie: Yeah. And a thief. I mean, he’s not the guy that invented the mouse. He picked up everything. He stole so many little things from Microsoft, from, you know, all over the place.

He had no class. Like, I have no respect for him. None.

But, Steve Wozniak was a great guy. He was a little older than us, just a little bit older than me, and we used to go over there if Steve Jobs wasn’t there to play Breakout on his prototype system.

So it was pretty fun.

Atari’s Party Culture

Tim Santens: Atari was known at the time for its big parties that it would have. Did you partake in that kind of culture that was there?

Steve Ritchie: Of course I did. I was like, you know, when I got there I was 24 years old.

Okay, this is unbelievable, but in Los Gatos, California, they didn’t care about weed at all. There was no law. Maybe there was, but nobody got arrested. I don’t know. Nothing was enforced. You could walk down the street and smoke a joint. So, every Friday, there would be this big tray of hash brownies. They were powerful.

I still picture my boss, John Petlansky [12] who’s dressed in a suit, coat, tie, and white shirt every day, eating two of the brownies. I mean, everybody was dangerously—I mean, dangerously—affected.

I had to work in burning ovens sometimes, in the early days. I just thought, “You know what, I don’t want to eat those and go in there” because there was all kinds of voltages at real high current and stuff like that.

“There was also cocaine snorted on the playfield glass, bottles of Red Mountain Wine, and Big Dog.”

So there was that, but you know, there was also cocaine snorted on the playfield glass, bottles of Red Mountain Wine [13] and Big Dog.

Steve Ritchie: Nolan [14] was a character. I liked him very much. It was interesting. That was the way in California. It was loose. That’s it. And also fun. I’m gonna say fun because it was.

Tim Santens: I bet! You can’t even imagine that kind of corporate environment anymore.

Steve Ritchie: Yeah, there was no corporation. When there was a corporation, they cleaned it up a bit. Like, you know, Warner bought them, [15] and that’s how we got the Superman license.

Video Game Crash of ’83

Tim Santens: When did you leave Atari?

Steve Ritchie: 1978. I think in April. I was there for four years.

Tim Santens: So you were there at the peak, and you got out before the video game crash of 1983. Did that affect the pinball market as well?

Steve Ritchie: The crash of ’83 was much later. I was already at Williams. What can I say about it? I don’t know. It didn’t matter to me. I was making pinballs, and pinballs were still selling, although a little bit less.

When you have a video game crash, a lot of businesses like distributorships lose a lot of money. So they don’t really have a lot to spend on pinball or anything else. And that’s exactly what happened. But, you know, it came back slowly.

There was a long time between when I left and the crash. It was like five years or so. In 1982, I started my own video game company and moved back to California. I had a contract with Williams to make two video games, and one of them was called “Chicken a la King.”

It was kind of a comedy, like a million ways to kill a chicken. The first microcomputer game we ever did was “Devastator,” a 3D flying game. It was very cool back in the day. But by the time we finished it, which was around 1983, the bottom fell out of the market.

The president called me up and said, “Steve, I can’t pay you.” I replied, “Well, that’s great news.” He then offered me to come back and make ten more pinball machines. So I did, and I went back to Williams.

Tim Santens: That’s good that you were able to transition back into pinball, which was still doing okay for you at that time.

Steve Ritchie: Yeah, it was going okay. But when I got back to the factory, it was dark because they had some bad games, and they didn’t sell well. The factory was practically empty.

High Speed

“I had a Porsche 928 and I went like 146 miles an hour… nine cop cars showed up in Lodi, California, and they’re all wondering how it’s ‘146’.”

Steve Ritchie: I mean I would say it was empty for two or three months, so I got hooked up with a new programmer named Larry DeMar, and we did High Speed together, which is based on a true story. I ran away from the cops. I didn’t really know the cops were behind me though. I had a Porsche 928 and I went like 146 miles an hour, and I went over a hill and here’s a highway patrolman, and my partner says to me, “Hey, slow down! There’s a highway patrol guy.”

So he went up the hill. This is five lanes in each direction on I-5 in California. It was brand new at the time. So he went over the mountain and I went down and cranked it up again. And a car came from the other direction, a sheriff’s car with a red light on. He turned around the median and I just pulled over.

I didn’t want to run. So he goes, “Just stay in the car.” So I did. I stayed in the car. And when the highway patrol pulls up, screeching into the gravel, he’s just acting all pissed off—I guess because he was. Then he tries to pull me out the window of my car and I go, “Officer, officer, wait, I can just get out.”

So, I open the door, get out, you know, he slams me down on the hood, puts handcuffs on me—the first and only time I ever got handcuffs or anything else—he threw me in his car, and then they started searching the car because I think they thought we robbed somebody or something.

So nine cop cars showed up in Lodi, California and they’re all wondering how it’s “146.” Well, the ticket said 120 mph plus because that’s as fast as his motorcycle could go.

Anyway, he got in the car after that, took the handcuffs off, and he goes, “Want a cigarette?” I go, “OK.” I did smoke, and he goes, “Why’d you do that?” I told the truth. I had the car for about two months, and I wanted to try it out. It’s early in the morning, and there’s nothing but tomato trucks in the right lane. If I came to traffic, I slowed down, but I wanted to see how fast it would go.

And he goes, “OK.” And then he says, “I don’t think you were running from me.” I wasn’t because I didn’t know he was behind me. Anyway, he held me in court. And the court was in session. If I didn’t go to court right then, I would have gone to jail. So I got taken to the court. They fined me $250. I lied and promised I would never go fast again.

Anyway, I built a game called High Speed around that. It had interesting speech and it was the first game with music, but it’s pretty pathetic by today’s standards. I mean I don’t like hearing it anymore. I had an idiot sound guy [Bill Parod] [16] who had no taste. He called rock and roll “hero music.”

And I played in a bunch of bands. I’ve been a guitar player since I was 13, and we got pretty far. We opened for Les Dudek [17] . Once, we opened up for the Doobie Brothers [18] .

But, I got tired of being poor, and that’s why I wandered into Atari. Although, we still had fans even though we were working, and one of them was with a bunch of people from Atari. The music, the music—I wrote the song, but it’s like, this guy, this sound guy goes, “That’s hero music.” You know, it was rock. His favorite kind of music was Javan drums. Like, who gives a shit? Who gives a shit about Javan drums? I mean, get out of here! He was like, an absolute obtuse weirdo. But, I would say he was a good person. Anyway, he wrote the music, and it took him a year, and it was bad—not wrote it, but translated it.

Mortal Kombat

Steve Ritchie: So let’s talk about more combat.

Tim Santens: Can you tell me a story about how you got involved with the game in the first place?

Steve Ritchie: Okay, I have done speech for many, many games way before Mortal Kombat. Lots of things. Just little stuff when people wanted something to be said, they were kind of bashful. I was not. I would go, how do you want me to say it? And I’d do what they asked me to do, you know. Different voices. I’m also the voice of Black Knight (1980).

Anyway, I had to do a couple of video games. The first one was Mortal Kombat. And Ed Boon [19] was a good friend. Actually, the first game he ever did was my game, F14 Tomcat (1987). It was the first commercial game he was ever involved in programming.

He was a great guy and very smart. We had a great time. He used to come over to my house and I had an Atari 1040ST computer. [20] He’d bring these three-and-a-half-inch floppies of all these games. He had one, I don’t remember, I think it was Executioner. The whole game was you had to cut this guy’s head off, and it would roll down the hill a little ways, and then this troll would come out and kick the head.

Creating the Mortal Kombat Name

“They had ‘Combat’ on the whiteboard, and I added the word ‘Mortal’… I added the K. No reason, it just looked cool.”

I think that was a pretty heavy influence on Ed because, you know, he wanted to make Mortal Kombat, but he didn’t know it was going to be Mortal Kombat. They had Combat on the whiteboard, and I added the word “Mortal,” and I don’t think they ever understood that that’s an old saying.

You know what I mean? When two people are locked in mortal combat, one’s gonna die, okay? And I added the K. I did nothing else on the game. No other programming or anything else except that and the speech. I was coached.

Tim Santens: What was the logic behind the K though?

No reason. I mean, it just looked cool. More a combat with a K.

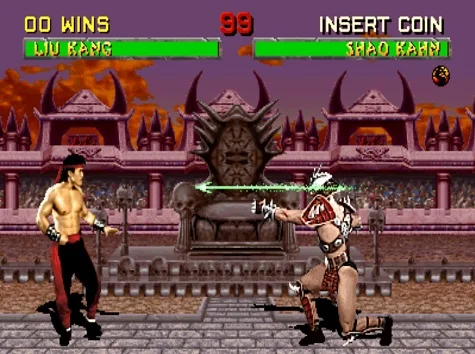

Steve Ritchie: Anyway, they said we want you to be a character called Shao Kahn. He’s Asian and kind of whispery, like “Mileena, Wins.” It’s very hard for me to do that now.

There was a great soundman there named Dan Fortin, and he is still with Ed Boon. And they are still making Mortal Kombat games, I’m sure you know. That’s been his whole career. Anyway, Dan Fortin coached me, and there were a few ad-lib things that I did, but mostly I stuck to the script. And my voice was lowered in pitch.

Like, I can still do, you know, pretty low stuff like, “Run home to mother, maggot.” “Finish Him.” You know, it’s like, it was hard to have energy, you have to be whispering. So we were in the studio and, I don’t know, I enjoyed it. I did Mortal Kombat 2 and 3, but not after that. Ed Boon didn’t like me anymore. I’m not sure why.

He didn’t ask me to do anymore.

Tim Santens: I think Mortal Kombat is interesting because at the time, it became the center of a lot of controversy, and due to the violent nature of the games, there were even congressional hearings. The line that you just mentioned, “Finish Him,” was the prelude to some of the most violent scenes that were pointed out by Congress in these hearings. What was that like to be in the middle of all of that controversy?

Steve Ritchie: It had no effect on me. I mean, I was sorry that it was happening to them, but it didn’t stop them. He didn’t stop anybody. I know not everybody liked that, but it certainly was unique.

And I have to say, it was a great seller for sure. Yeah, it was pretty hard. You know, when you have public demand like that, I mean, some people will complain.

“I would never make a pinball machine like that now because I don’t want anybody not playing my game for any reason. And that includes kids.”

I would never make a pinball machine like that now because, well, they can get away with it because they have history. I wouldn’t try it because I don’t want anybody not playing my game for any reason. And that includes kids.

I’ll say run home to mother, maggot, and a few other insult things, but there’s no heads being cut off in my games.

Tim Santens: For sure. I think the last game you contributed to was, 2005’s Mortal Kombat. Shaolin Monks. Was that the last Mortal Kombat one you participated in?

Steve Ritchie: No. No. I only did two and three. That’s somebody else.

People like my voice, apparently, but Ed Boon never wanted me back, and that was okay with me. I have a career here.

Working with Intellectual Property

Tim Santens: Can you talk about working with big intellectual property, like Star Wars and Spider-Man? What’s it like working with these companies who are very protective of their IP?

Steve Ritchie: We’re talking a wide range of stuff. With Superman, there were no restrictions whatsoever. They didn’t really care. I suppose if we wrote curse words on the inserts or something, we might have gotten in trouble. But there was nothing about that.

I’m trying to remember the next licensed game I got. You know, when I was there, when I first started working at Pinball [for Atari], they didn’t care about licenses. Bally did. And they made good money on them, but then their games were kind of not that cool.

Terminator 2 (T2)

Steve Ritchie: Terminator 2 was a great license. Incredible. Three of us—it was Dwight Sullivan and Greg Freres. Dwight Sullivan [21] was a programmer. Greg Ferraris. No, not Greg Ferraris. [22] Another guy, the artist Doug. Doug Watson. [23] We were invited to Lightstorm Studios, and this is mind-blowing.

We spent three hours with Jim Cameron. He was totally into games.

I don’t know if you know this, but he lived in his car when he wrote the first Terminator movie. He had nothing until that movie hit. And T2, great story. We got it and it was just an outstanding license where they sent us the terminator arm in a glass tube.

We got that for a couple of weeks. Then we had the chip part and Chrome skulls. Anyway, we got dailies of everything they filmed. That’s never going to happen again with dailies. We watched Arnold Schwarzenegger riding on the top of this upper part of the L.A. drainage system, and there are cables and everything, and this standing guy is riding the bike, but the bike’s being carried by cables down the bottom. It’s an incredible scene. It was a great license.

They gave us as much as they could. Terminator 2 Judgment Day Pinball was in theaters on the 4th of July, the day they opened. All across the United States. I had one year to make the game. I had a great team though. Lots of good people. We got music, likeness, and whatever we wanted. We couldn’t do footage though because it was Dot Matrix display only.

T2 was supposed to be the first game with this dot matrix, you know. We had no display before. We were spelling out things alphanumerically in these little eight-segment displays. And that was a whole world. I wanted that bad, but again, somebody said, well, “Gilligan’s Island isn’t looking that good, so we’d like to use the dot matrix display in that game first.” It’s no big deal. Anyway, it was a great license.

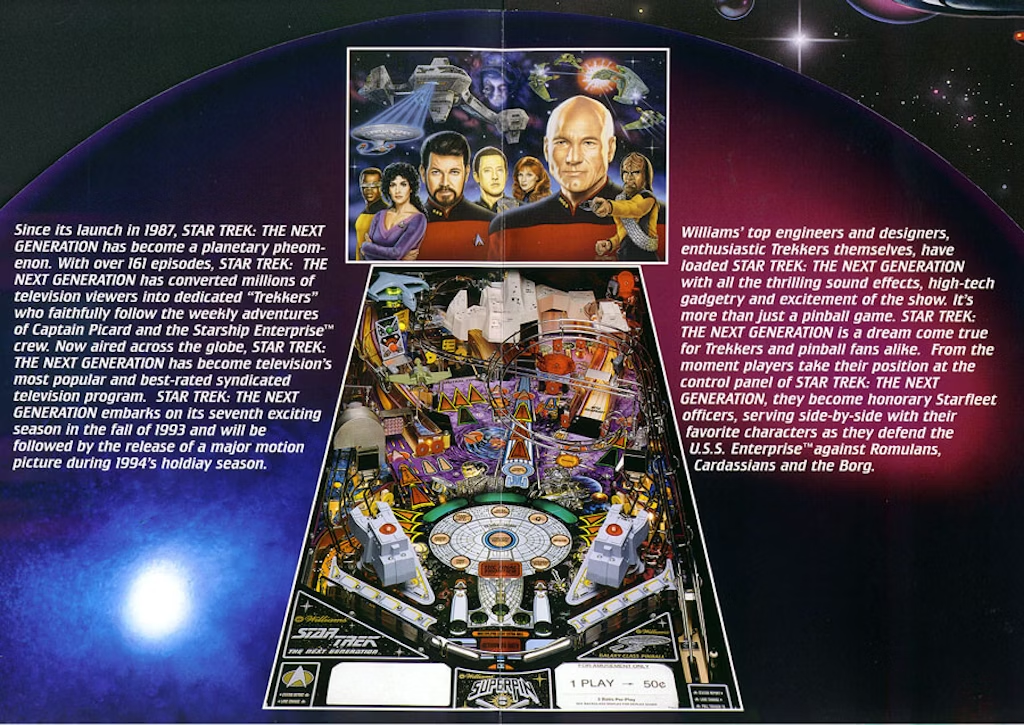

Star Trek

Steve Ritchie: I’m trying to think of the next licenses. Okay. Star Trek.

For Star Trek we went down to Los Angeles to Paramount Studios. You walk in and they give you a lecture on how you’re not allowed to talk to any stars unless they talk to you. So, we’re walking through, and we see Kelsey Grammer. And he goes, hi guys! So we got to talk to him, he was cool. And then after that, we watched one of the last episodes of Cheers being filmed.

And then finally, we start to meet guys like Michael Okuda [25] , the guy that’s sort of in charge. Anyway, we sat down with these three ladies who were from licensing.

We’re talking, and we’re thinking, we’re getting excited because we got to see sets from Deep Space Nine, which was scheduled to be made. And just, you know, we went to the bridge and the only thing we couldn’t do was sit in the chairs. You walk behind the bridge and you realize, wow, this is made of plywood and they got lights with bulbs and spinning wheels back here and they’re motorized.

Kind of fakey, but I mean, you know, you don’t think about that when you’re watching the show. So we go eat lunch, and guess who sits right behind me? Patrick Stewart. And his pipes are so awesome. I mean, even now, but back then, I mean, he just had this magic in his voice, just awesome.

I couldn’t say hi. I couldn’t do anything. I didn’t even turn around and look at him until he walked out. But, Kirstie Alley was across the way and I smiled at her and she smiled back.

So these three women are talking about what our limitations are. The third thing they say is, “You know, we don’t want any phaser firing or photon torpedoes.”

What? And I go, “You have to be kidding. That’s not real, is it?” And she said, “Yes, it’s real. You can’t do that.” And I said, “I don’t see how that could be. Everybody on this team knows the prime directive. And the captain would never fire on anyone unless he was provoked.” I didn’t want to make a namby-pamby game.

“I can’t do this if you’re gonna hang with this.” And they said, “That’s the rule.” So, we walked out. We went back to Chicago and a couple weeks later, Roger Schrupp, who was in charge of licensing, calls up and says, “How can we salvage this?” So, we went back out.

It turns out those three ladies were fighting for the top position. They moved all of them out of licensing and there was one lady named Susie Dominic, and she said, “Make the game the way you want, within the Star Trek realm.” So we did, and it was a great relationship from then on, it was awesome. It’ll never happen again where you get the whole crew participating, all of them.

It was amazing, including Q, okay? All the voices are there—Patrick Stewart, Brent Spiner, Jonathan Frakes. Basically, all the characters. So that was fun as hell, and it was a great game. It was the last five-digit run of any pinball machine.

Nothing’s gotten into the five digits since then.

I really have to run.

Tim Santens: Well, I appreciate you taking the time out of your day to talk to me. Thank you very much.

Steve Ritchie: You’re welcome, man. I try to help everybody I can. Good talking to you, Tim. I wish you the best.

Tim Santens: Thank you.

Footnotes

1. When components in manufacturing and assembly fail quality tests at any point in the production process.

2. Atari entered the pinball market in 1975 to diversify its offerings and address concerns within the arcade industry. Despite pioneering video game entertainment with titles like Pong, Atari’s newer games were not always generating the same level of interest or revenue. In fact, by 1975, the average video game earned only around $43 per week, which was less than what billiards tables made, worrying arcade operators. Although founder Nolan Bushnell had originally envisioned a future where video games would replace pinball, the company saw the need to embrace traditional arcade entertainment to remain competitive. This led to the formation of Atari Pinball, with the goal of merging their video game innovation with the classic appeal of pinball.

3. Airborne Avenger is a super widebody and was the very first pinball machine designed by the great Steve Ritchie, presented in September of 1977. It featured electronic sound, even at a time when ‘the big 4’ manufacturers were still using chime units.

4. Gary Slater was a pinball designer known for his work on classic Atari pinball machines during the late 1970s. He designed Middle Earth, released in February 1978, and Space Riders, released in September 1978.

5. Eugene Jarvis is a renowned video game and pinball designer best known for his pioneering work in the arcade gaming industry, particularly with Atari and Williams Electronics. Starting his career at Atari, Jarvis contributed to some of the earliest innovations in video game design before moving to Williams, where he became famous for creating iconic titles like Defender and Robotron: 2084. His deep understanding of game mechanics and player engagement not only influenced video games but also the pinball industry, where Williams thrived. Jarvis’ impact on both fields solidified his reputation as one of the most influential designers in arcade history.

6. In 1996, Williams Entertainment, a subsidiary of WMS Industries, acquired Atari Games, marking a significant merger in the arcade gaming industry. This acquisition brought together two major forces in arcade entertainment, with Williams known for its pinball machines and innovative video games, while Atari Games had established itself as a leader in arcade video games since its founding by Nolan Bushnell in the 1970s. By acquiring Atari, Williams expanded its portfolio, gaining access to a wide range of popular Atari titles and technologies. The merger allowed Williams to strengthen its position in the rapidly changing gaming market, especially as the industry began shifting more towards home consoles and digital platforms.

7. California Speed is a racing video game developed and published by Atari Games. The game was first released in arcades in 1998 and was ported to the Nintendo 64 in 1999 by Midway.

8. International Game Technology (IGT) is a global leader in the design, development, and manufacturing of gaming and lottery systems, best known for its slot machines and innovative gaming technologies. Founded in 1975, IGT has revolutionized the gaming industry with products that include electronic gaming machines, central systems, and interactive gaming solutions. Its pioneering work in video slots, particularly with its Wheel of Fortune and Megabucks series, has cemented its position as a dominant force in casinos worldwide. IGT’s operations span multiple continents, and the company continues to innovate in areas such as mobile gaming and digital platforms, ensuring its relevance in both traditional and modern gambling environments. Through acquisitions and continuous development, IGT has expanded its reach, integrating lottery and sports betting into its offerings, making it one of the most influential players in the global gaming landscape.

9. Gary Stern is a prominent figure in the pinball industry and the founder of Stern Pinball, Inc., the world’s leading manufacturer of pinball machines. Coming from a family deeply rooted in pinball, Gary’s father, Sam Stern, was a co-owner of Williams Manufacturing. Gary continued the family legacy by working in the industry from a young age and eventually founding Stern Electronics in 1977, later transitioning into Stern Pinball in the 1990s. Under his leadership, Stern Pinball became the last remaining manufacturer of pinball machines during a time when the industry was struggling, keeping the art and tradition of pinball alive through classic and modern-themed machines. Gary Stern is recognized for his dedication to evolving pinball gameplay while maintaining its nostalgic appeal, securing Stern Pinball’s status as an essential player in the arcade entertainment world.

10. In 2009, Dave Peterson, co-founder of a private equity firm, became a significant partner and investor in Stern Pinball, contributing to the company’s financial revival during a challenging period. Peterson’s business expertise, particularly in finance, helped stabilize Stern Pinball, allowing it to recover from near closure and continue producing new machines. This partnership marked a turning point for Stern Pinball, as Peterson’s financial acumen complemented Gary Stern’s leadership, paving the way for the company’s continued success.

11. Lyman F. Sheats Jr. (March 24, 1966 – January 19, 2022) was a highly respected and influential figure in the pinball industry, known for his exceptional skills as both a game designer and software programmer. With a career spanning multiple decades, Sheats worked for leading companies like Williams, Bally, and Stern Pinball, where he made significant contributions to some of the most beloved pinball machines of all time. His mastery of pinball rules and gameplay design elevated titles such as Attack from Mars, Medieval Madness, and Monster Bash, earning him a legendary status among pinball enthusiasts. Sheats was also known for his deep passion for the game, often competing in pinball tournaments and refining his designs to create engaging, immersive experiences. His work had a lasting impact on the industry, and he is remembered as one of the greatest pinball programmers and designers in history.

12. John Petlansky served as the production manager for Atari’s printed circuit board (PC) plant, which was established in Sunnyvale, California, in the mid-1970s. He played a crucial role during Atari’s rapid expansion in the arcade and pinball industries. His leadership at the facility helped Atari meet the increasing demand for its products, which included iconic arcade games such as Pong and early pinball machines. This facility was part of Atari’s larger strategy to streamline production and meet the growing needs of the coin-operated gaming industry. Petlansky’s efforts were pivotal in ensuring the smooth operation of Atari’s manufacturing processes during a period of significant technological advancement and high demand for arcade games.

13. Red Mountain Wine was a popular, inexpensive jug wine in the 1960s and 1970s, produced by Almaden Vineyards in California. Known for being sold in large gallon jugs, Red Mountain was associated with college parties and budget-conscious consumers. It wasn’t known for its quality, but rather for its accessibility and affordability, becoming a staple among those looking for cheap wine in large quantities. The wine was a simple, mass-produced table wine that found a place in homes and gatherings where the emphasis was more on quantity than on the refinement of taste.

14. Nolan K. Bushnell is a pioneering entrepreneur best known for founding Atari, Inc. in 1972, revolutionizing the video game industry. Often regarded as the father of video gaming, Bushnell’s creation of Pong, Atari’s first major hit, laid the foundation for arcade gaming as a cultural phenomenon. Under his leadership, Atari expanded its influence with groundbreaking arcade games and the release of the Atari 2600, which became one of the most iconic home gaming consoles of the 1970s and 1980s. Bushnell’s vision of bringing electronic entertainment into homes and arcades helped shape the early gaming landscape, establishing Atari as a dominant force in the industry. His innovative approach to both technology and business made him one of the most influential figures in gaming history.

15. Warner Communications acquired Atari, Inc. in 1976 for an estimated $28 million, marking a pivotal moment in the company’s history and the gaming industry. At the time, Atari had achieved success with Pong and other arcade games, but the acquisition by Warner provided the financial backing and resources needed for Atari to scale its operations and develop new technologies. Under Warner’s ownership, Atari launched the Atari 2600 in 1977, a home video game console that revolutionized the gaming market and became a cultural icon. However, despite early successes, tensions between Atari’s creative leadership, including founder Nolan Bushnell, and Warner’s corporate management led to Bushnell’s departure in 1978. The acquisition played a critical role in Atari’s meteoric rise, but it also set the stage for challenges that would come later as the gaming market evolved.

16. Bill Parod contributed to the High Speed pinball machine, released by Williams Electronics in 1986, by composing the music and working on the sound effects alongside Eugene Jarvis and Steve Ritchie. High Speed was one of the first pinball machines to use digitized music, a technique Parod had previously worked with on Grand Lizard. His work on the audio complemented the fast-paced, police-chase-themed gameplay, helping to create a cohesive experience for players.

17. Les Dudek is an American singer, songwriter, and guitarist known for his work in rock and blues. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Dudek collaborated with several iconic artists, including the Allman Brothers Band, Boz Scaggs, and Steve Miller Band. His guitar work contributed to tracks like “Ramblin’ Man” and “Jessica” from the Allman Brothers, as well as on Boz Scaggs’ hit album Silk Degrees. In addition to his collaborations, Dudek pursued a solo career, releasing several albums that showcased his blend of rock, blues, and jazz influences. His distinctive guitar style and soulful vocals have earned him a lasting reputation in the world of classic rock.

18. The Doobie Brothers are an iconic American rock band, known for their blend of rock, soul, and R&B influences. Formed in 1970 in California, the group gained widespread popularity in the 1970s with hits like “Listen to the Music,” “China Grove,” and “Long Train Runnin’.” Their sound was defined by tight vocal harmonies, intricate guitar work, and a mix of acoustic and electric elements. The band saw a shift in their style after Michael McDonald joined in 1975, introducing a more soulful, keyboard-driven sound that led to hits like “What a Fool Believes” and “Takin’ It to the Streets.” Despite lineup changes over the years, The Doobie Brothers have remained a lasting force in classic rock, earning a loyal fan base and induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020.

19. Ed Boon is a prominent video game designer and programmer, best known as the co-creator of the Mortal Kombat franchise. Starting his career at Midway Games in the late 1980s, Boon worked on pinball games and arcade classics before collaborating with John Tobias to create Mortal Kombat in 1992. The game became an instant hit due to its unique fighting mechanics, digitized graphics, and controversial use of graphic violence, particularly the iconic “Fatalities.” Boon has remained a key figure in the gaming industry, continuing to lead development on the Mortal Kombat series under NetherRealm Studios, which was formed after Midway’s closure. His contributions have cemented Mortal Kombat as one of the most influential and long-running fighting game franchises in history.

20. The Atari 1040ST, released in 1986, was a groundbreaking personal computer in the ST series developed by Atari Corporation. It was one of the first mass-produced computers to feature a full 1 MB of RAM, which was notable at a time when most consumer computers offered significantly less. The 1040ST was part of Atari’s ST line, which was aimed at competing with systems like the Apple Macintosh and Commodore Amiga. The computer was equipped with a Motorola 68000 CPU and ran the GEM (Graphics Environment Manager) operating system, offering a graphical user interface (GUI) that appealed to both general consumers and professionals.

21. Dwight Sullivan is a veteran pinball game developer known for his work on programming, code, and mechanics for a range of iconic pinball machines. With over 30 years of experience, Sullivan has worked for top manufacturers like Williams, Bally, and Stern Pinball. He is best known for his contributions to popular games such as Star Wars, Game of Thrones, Ghostbusters, and Terminator 2. His expertise lies in crafting complex and engaging rulesets that enhance gameplay.

22. Greg Freres is a renowned pinball artist and designer with a career spanning from 1979 to the present. He has worked with major manufacturers like Williams, Bally, and Stern Pinball. Known for his distinctive art style, Freres contributed to several iconic machines, including Medieval Madness, Monster Bash, and Elvira’s House of Horrors. His contributions include art design, callouts, and concept development, making him a key figure in the evolution of pinball esthetics.

23. Doug Watson is a well-known pinball artist who contributed to many classic machines during his career, particularly during his time at Williams Electronics. Some of his most recognized works include The Machine: Bride of Pin-Bot, Black Knight 2000, and The Getaway: High Speed II. Watson’s distinctive art style helped define the visual identity of many popular pinball games, and he has been highly regarded for his ability to create immersive, dynamic designs that enhance the overall player experience.

24. Lightstorm Entertainment is a film production company founded by director James Cameron in 1990. The studio is best known for producing some of the most successful and visually groundbreaking films in history, including Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Titanic, and Avatar. Lightstorm is known for pushing the boundaries of special effects and technology in filmmaking, especially with its use of CGI and motion capture. The studio’s focus on innovation has earned it a reputation as a leader in the film industry for producing blockbuster hits.

25. Michael Okuda is a graphic designer and illustrator best known for his work on the Star Trek franchise. He joined the Star Trek team in the 1980s and became famous for creating the futuristic user interfaces seen on the bridge consoles of starships, commonly known as “Okudagrams.” His work helped define the visual aesthetic of Star Trek: The Next Generation and its subsequent series and films. Okuda also contributed to the development of technical manuals, including the Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual.